Where Do Fish Belong?

The way we discuss our ecological problems, like invasive species, can limit our view of available solutions.

❖

By Kathleen Blackburn

7 min read

FISH

Act Now

↓Stories tell of throngs of Asian carp swiftly heading up the Mississippi toward the Great Lakes, bursting through river surfaces and overcoming obstacles.

The carp are considered an invasive species. But does this view help us understand the problem? How can we develop solutions that don’t rely on the systems that made the carp’s migration possible in the first place?

Four fish and a river

The term “Asian carp” actually refers to four different carp species. Grass carp were originally imported from Malaysia in 1963 to catfish farms in Arkansas to replace chemical weed control. Within ten years, the three other species – Silver, Bighead, and Black carp – were released into the Arkansas waterways in an experiment to clean the state’s waterway system. When funds for the experiment expired, the Silver and Bighead carp were freed into Arkansas streams, and they soon made their way into the Mississippi.

The Silver and Bighead thrive off the density of plankton. We tend to think of all Asian carp as the Silver, which leap out of water in response to the vibrations from boat engines and jet skis. The Bighead and Black carp are much less visible, hovering near the riverbed. Silver and Bighead eat plankton, while Black carp feed on mussels. All are swimming upstream toward the Great Lakes.

An engineering marvel meets a force of nature

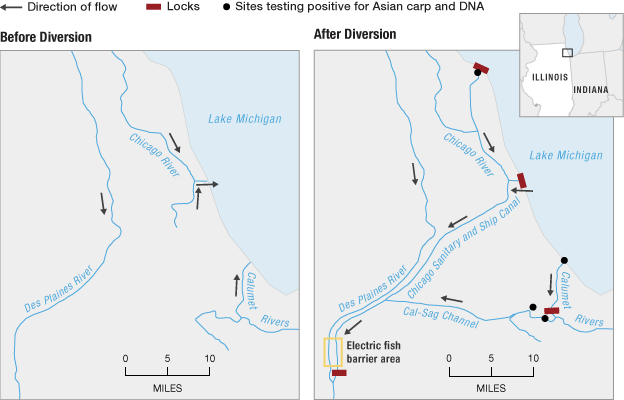

The very channel that makes it possible for Chicago to ship its waste downstate into the Des Plaines River and onward to the Mississippi basin has become what some call the “highway” for Asian carp to reach Lake Michigan.

Prior to 1900, the city of Chicago once ran its sewage and other pollutants into Lake Michigan through the Chicago River. In response to concern over drinking water, a series of canals were built to reverse the direction of the Chicago River’s flow so that sewage discharge no longer ran up into Lake Michigan but rather down into the Des Plaines, Illinois, and finally the Mississippi. The Society of Civil Engineers celebrated the elaborate infrastructure of locks and canals that connect Lake Michigan to the Mississippi as the “Engineering Monument of the Millennium.”

Straightening the South Branch between Polk and Taylor Streets. From The Lost Panoramas: When Chicago Changed its River and the Land Beyond by Richard Cahan and Michael Williams, from City Files Press

The infrastructure of the Chicago Area Water System is thus the site for two kinds of stories: one of technological ingenuity and another of a threatening invasive species. Yet, the language we use to describe the fish obscures the infrastructural developments that have made their movement upstream possible. If these developments mobilized the carp’s upstream path, must we continue to rely on canals, dams, and barriers to contain the carp?

What's at stake

The carp are voracious eaters. The Silver and Bighead devour nearly 20% of their bodyweight in plankton per day, and they tend to out-eat fish that originally inhabited the bodies of water they reach. Unlike the Bighead and Silver, Black carp consume mussels, but are equally ravenous. They also reproduce prolifically; some areas of the Mississippi are considered to be more than 90% Asian carp in biomass. Many of us understand that if the carp reach the Great Lakes, they could potentially devastate the existing multibillion-dollar fishing economy, including the native trout. Members of the House and Senate Great Lakes Task Force claim that carp pose one of the greatest challenges to the region, and leaders in the Great Lakes Commission believe that action to stop them should be taken immediately.

Building walls in the water

Most efforts have taken the form of physical obstructions. Between 2002 and 2009, the Army Corps installed three different electric barriers within the Chicago Sanitary Canal. The barriers, located approximately 35 miles south of Lake Michigan, generate an electric field that is supposed to prevent carp entry into Lake Michigan

Though the carp have not established a presence in the waters north of these barriers, as far as we know, DNA testing has shown traces of the carp in the Chicago River only a block from Lake Michigan’s shore. More urgently, on June 22, 2017, an adult Bighead Carp was found only nine miles from the Lake, having evaded three barriers.

After shelving the release of the Army Corps’ most recent initiative to stop Asian carp, the Trump administration released the report in August 2017. The Corps’ proposal focuses on the Brandon Road Lock and Dam near Joliet, Illinois – a site many consider to be a strategic point in blocking the carp – and presents a plan to develop electric underwater barriers, noise deterrents, and an elaborate water jets to the cost of approximately $275 million.

With the Trump administration’s threats to defund the Great Lakes Restoration Project and the Army Corps’ plans to impede the carp with new electric barriers indefinitely deferred, the perils surrounding Asian Carp continue to deepen. DNA testing from the last few years suggests that the carp are able to travel past the barriers, and many researchers fear that by the time we realize the carp have reached the Lakes, it will be too late to take any impactful action.

What we talk about when we talk about Asian Carp

Their strong appetites, combined with images of their large eyes, hollow mouths, and spectacles of leaping, are characteristics that have been used to represent Asian carp as a threat – but without much impact on stopping their movement toward Lake Michigan. Terms like non-native and invasive tend to vilify the carp rather than help us consider the structural pathways that connect the Mississippi to the Great Lakes and reconsider our approach to the issue.

The term invasive suggests that these carp threaten to disrupt an original ecosystem, creating a distinction between fish that belong and those that don’t. But the Great Lakes are home to over 180 species that weren't here when European settlers arrived. This isn’t to say that the presence of the carp wouldn’t be intrusive, but to broaden the conversation beyond belonging and not-belonging. If the problem is limited to an invasion, actions will continue to be relegated to military-style intervention and infrastructure – like walls. How might a change in language broaden our engagement with the carp issue?

What if, instead of metaphors based on conflict, we looked at the problem from the perspective of ecology? Ultimately what we desire is an ecosystem that can flourish, where ecological services such as pest control, water filtration, and food production (to name just a few) do not disrupt each other, nor the lives of other species that we consider wild. In this way, we can re-examine the impacts of the pathways we open to ship commodities. When the flow of product is the highest priority, the sources of our drinking water and home to aquatic species are diminished.

How does language shape action?

The problem of Asian carp doesn’t just raise ecological concerns. It asks us to think about how words influence our agency. While the carp are poised to disrupt the Lakes’ current ecosystem, we have an opportunity to reshape our relationship to them through the language that represents their presence.

For example, the carp are often considered unappetizing. In part this stems from confusing Asian carp with the common European carp, which have a muddy flavor. But it also results from the stigma of the word carp, which many Americans associate with being dirty. Hence, there have been efforts to rebrand the Silver carp as “Silverfin,” similar to how the Patagonian Toothfish became Chilean Sea Bass and Orange Roughy was once known as Slimehead, suggesting that our solutions are influenced by the words we use.

What can we do?

Reimagining the story of the carp as that of a migrating species swimming up a pathway of our own design shifts our attention away from the distraction of stigmatizing the carp. Instead, we can focus on solving the problem of artificially connecting two watersheds, and on strengthening ecological services.

→ Act Locally

The spread of exotic species is often accidental. If you enjoy boating or fishing, you can help avoid it through a few simple actions:

Clean, drain, and dry your boat after each use.

Wait three days between using the same equipment in different bodies of water.

Choose the right fishing bait.

Join an invasive species pull.

Contact your local Fish & Wildlife office for more information on how you can help in your area.

→ Reclaim the Chicago River

The network of canals, locks, and dams that created the pathway for the carp doesn’t have to be permanent. Restoring the natural divide between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi will not only prevent the carp’s access to the basin, but also revitalize the Chicago River.

Where 19th and 20th century infrastructure enabled Chicago to develop an enchanting front yard of public parks and beaches, we now need 21st century infrastructure that secures the health of all waterways. The Freshwater Lab envisions a water recycling plant along the Chicago Area Water System where nutrients (like the nitrogen and phosphorus necessary for growing food) are reclaimed while Chicago’s effluent becomes usable water for agriculture and industry. Not only can such a new approach to waste can generate more available water and create jobs, but it can also enable the separation of the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River – a necessary step to protecting the lakes from the carp.

Learn more about the proposed plan to reclaim the Chicago River.

→ Eat the Fish

Asian carp are a plentiful and nutritious source of protein, but because they are seen as non-native and ecologically damaging, most Americans shy away from integrating carp into their kitchens. However, there are several efforts to repurpose the carp as a good source of local food.

You can start with one of our favorites:

Asian Carp Burgers

(courtesy of Dirk's Fish)

Ingredients

- 2 pounds Asian Carp fillets, ground

- ½ cup panko bread crumbs (optional)

- 2 tablespoons fresh garlic, chopped

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- 1 tablespoon lemon zest

- 4 teaspoons dry oregano or 2 teaspoons fresh oregano

- 2 teaspoons black pepper

- 1 ½ teaspoons kosher salt

- ½ teaspoons nutmeg

Directions

- Combine all ingredients except panko crumbs. Grind the fish twice to make sure there are no more bones and to mix-in spices. Add panko crumbs and form into patties or choose not use breading. The burgers will be a little softer but just handle with care.

- If you want to add cheese, use a soft cheese. Form a small ball of cheese and insert into the center of the burger. Form the burger around the cheese.

- Cook for about five minutes per side on a hot grill; the cheese will start leaking out when they are almost done.

Head over to cantbeatemeatem.com for more recipes.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories