Turning Our Waters Green

What we grow and how we grow it determines the health of our waters.

❖

By Stephen Gasteyer

10 min read

FARMING

Act Now

↓In recent years, we’ve seen portions of the Great Lakes turn green from harmful algal blooms over and over again.

In Lake Michigan, the problem is most pronounced in Green Bay, but nothing sounds alarms like the increasing algal blooms in Lake Erie, the shallowest of the Great Lakes. Cities such as Cleveland and Toledo have even had to shut off their water supply when the blooms became extreme. During an outbreak, people are paralyzed, and authorities offer few solutions. If the causes and effects are so well known, why have we failed to address the problem?

A familiar issue

Cyanobacteria such as green algae can produce toxins that are harmful or fatal to humans. Photo: Jeff Reutter

Algae are naturally found in water bodies all over the world, and form the foundation of most aquatic food chains. The most common freshwater algae are green algae, diatoms, and blue-green algae, some of which can produce powerful toxins known as cyanotoxins. Toxic algal blooms involving a cyanotoxin called microcystin can sicken or even kill humans and animals. Additionally, when the algae die off, their decomposition can consume large amounts of oxygen in the water, causing "dead zones" where other species can't survive.

It’s common knowledge that agriculture is the primary source of the nutrients that feed algae growth. Fertilizers and manure from agriculture fields and combined agricultural feeding operations (CAFOs) contain high amounts of nitrogen and phosphorous. When rainfall and snowmelt wash fields, they carry these nutrients into streams that flow into the lakes and cause the neon green algae to bloom.

We now understand the relationship between agriculture and algae well enough to accurately predict seasonal blooms. This situation calls into question the relationship between agriculture and the Great Lakes region.

Extreme farming is the norm

Agriculture has been a major part of the land use and human production systems in the Great Lakes for a very long time. However, not all agriculture is the same, nor do all forms of agriculture have the same impacts on the land and water.

There are four main types of modern agriculture:

-

Industrial (or conventional) agriculture focuses on producing particular commodities – such as corn or soybeans, livestock, or intensive fruit or vegetable production. This type of agriculture favors high volume, as each individual plant has low value to the farmer. To achieve the high volume, it generally involves inputs external to the soil, land, or plants – in the form of machinery, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, confinement facilities, and in the case of livestock, fruit, and vegetables, hired labor.

Almost all of what is produced and sold goes into the commodity system – the system of processors, distributors, wholesalers and suppliers that transform raw materials into products sold to consumers in supermarkets throughout North America and globally. For example, a diverse set of products including feed for animals, high fructose syrup, ethanol, corn chips, and biodegradable plastics, use corn as a key ingredient.

-

Organic agriculture is a system of farming that is based on minimized chemical inputs and tends to be used in the production of produce (fruit and vegetables) and livestock (meat and dairy) – although farmers in the Great Lakes also produce organic corn and beans. Organic certification requires farms to commit to certain practices and to annual inspection. In the Great Lakes, many of these farmers specialize in fruit and vegetables and market to consumers through farmers’ markets or other non-mainstream distribution systems, groceries, and wholesalers.

-

Low-input agricultural producers use practices similar to organic agriculture, but are not certified and occasionally apply external inputs when necessary to ensure production. These farms vary in size, but are generally dependent on a direct relationship with consumers. They tend to produce fruit, vegetables, and other low volume, higher value products, and distribute through farmers’ markets and other similar venues.

-

Subsistence agriculture is a form of agriculture that aims to produce enough only for a family or a surrounding community. Farmers of this type of agriculture are least concerned about agricultural markets and tend to minimize external inputs, as the production does not generate income. They are often associated with food sovereignty efforts in marginalized communities.

Industrial agriculture dominates the food production system today, accounting for over 95% of food sales in the US. Thus the methods – and financial incentives – of large-scale industrial food production define the modern system.

Transforming the land and the water

According to both Tribal records and those of the European expeditions in the 17th century, the native peoples of the Great Lakes cultivated crops such as corn, beans, peas, squash, and pumpkins, as well as gathering of wild rice, among other medicinal and food crops. This system only changed the landscape in relatively minor ways, but was critical to vibrant, complex societies that existed prior to European arrival.

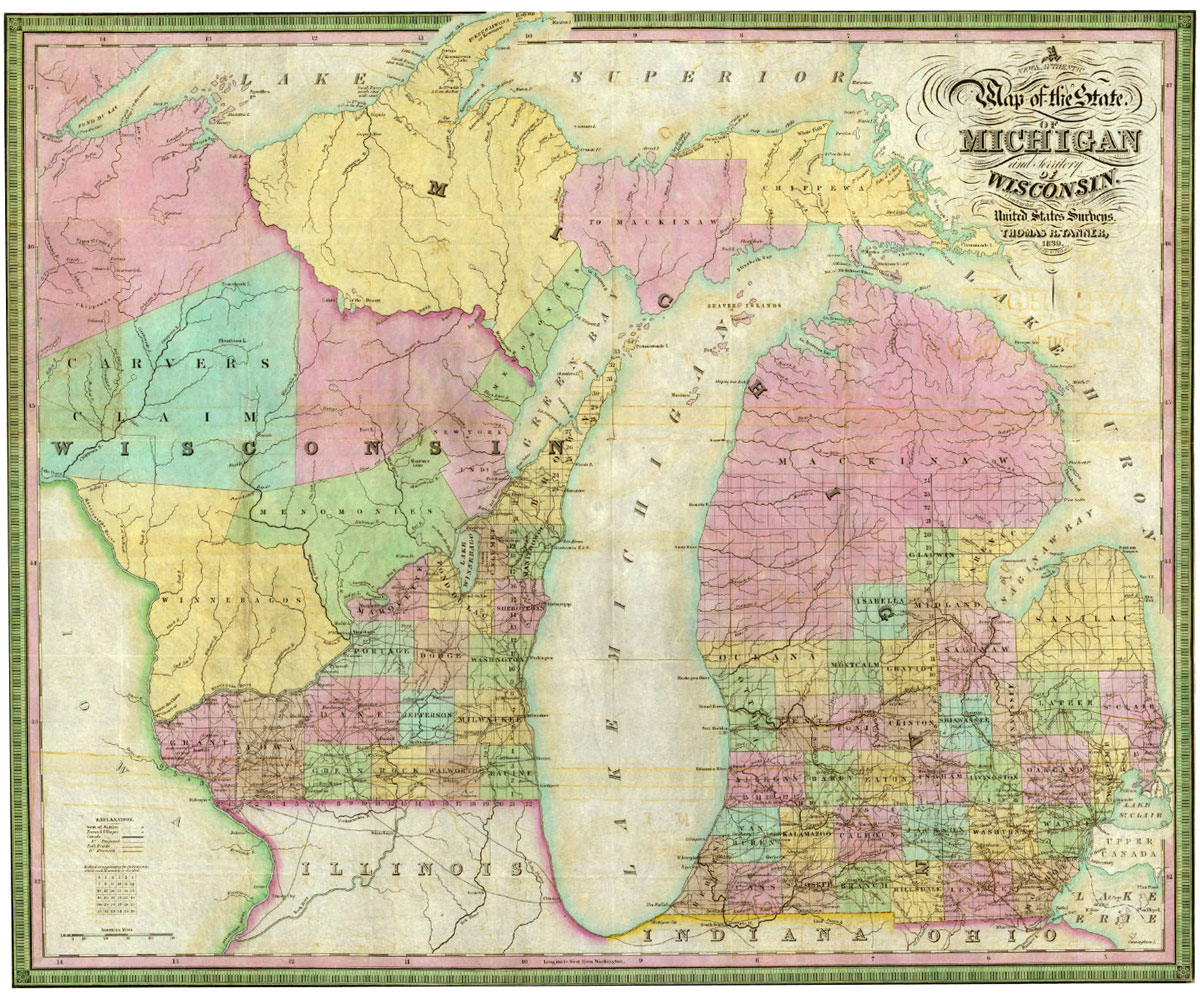

Euro-American settler farmers established small farms as they moved west to settle in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and in Canada into Ontario in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Eventually, these farmers moved into Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana in the 18th and early 19th centuries. These were initially small, relatively low-input farms that produced a combination of subsistence and market crops. Still, the farming techniques they used involved clearing forested land, and later draining wetlands. Some scholars argue that placing these farmers more permanently on the land was part of an American Government strategy to occupy the Northwest Territory states as the United States moved to the west.

Establishing farms in the Great Lakes region was part of the American project of expansion, as seen on this map of Michigan and Wisconsin from 1839.

These actions transformed the landscapes – converting the flatland forests of the southern Great Lakes into millions of acres of farmland. Farms were initially diverse, and supplied a major part of the sustenance for farm families, but were also established as commercial endeavors based on production of corn and hogs in the United States, and wheat and livestock in Quebec and Ontario. Throughout the 1800s, the federal, state, and provincial governments established institutions, such as the Michigan Agricultural College (later Michigan State University) and other “land grant universities,” to provide settler farmers with the scientific knowledge and technologies to adopt more efficient commercial farming practices. Productivity from these farms was critical to the development of nearby industrial urban areas.

These institutions participated in developing a commercial agricultural economy through the Great Lakes states that complimented the trade system for other commodities such as wood and minerals. The engineering of and creation of commercial shipping routes across the Great Lakes – with the development of Erie Canal, Saint Lawrence Seaway, and the Sault Sainte Marie Locks – created a mechanism for transport of agricultural products and other commodities (including logging and iron ore) across the United States and globally.

The development of this system involved the designation of distinct agricultural zones within the Great Lakes region. Over time, some of the zones have changed – Ontario has transformed in response to pricing from wheat to corn, for instance – but these general designations are still in place today.

The big business of growing

As a sector, agriculture is extremely important to the Great Lakes economy, accounting for more than $15 billion in annual cash receipts. Livestock plays a particularly important role, with dairy alone accounting for roughly $5 billion annually, and supplying 15% of the US dairy consumption.

The production of agriculture, however, varies across Great Lakes states and provinces. In Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, for instance, (as well as the Canadian province of Ontario) row crops and livestock production systems dominate the agricultural sector. Michigan and New York, on the other hand, have more mixed cropping systems – with significant acres in orchards, vineyards, and vegetable farms.

Farming in the Great Lakes varies by region but generally uses conventional methods.

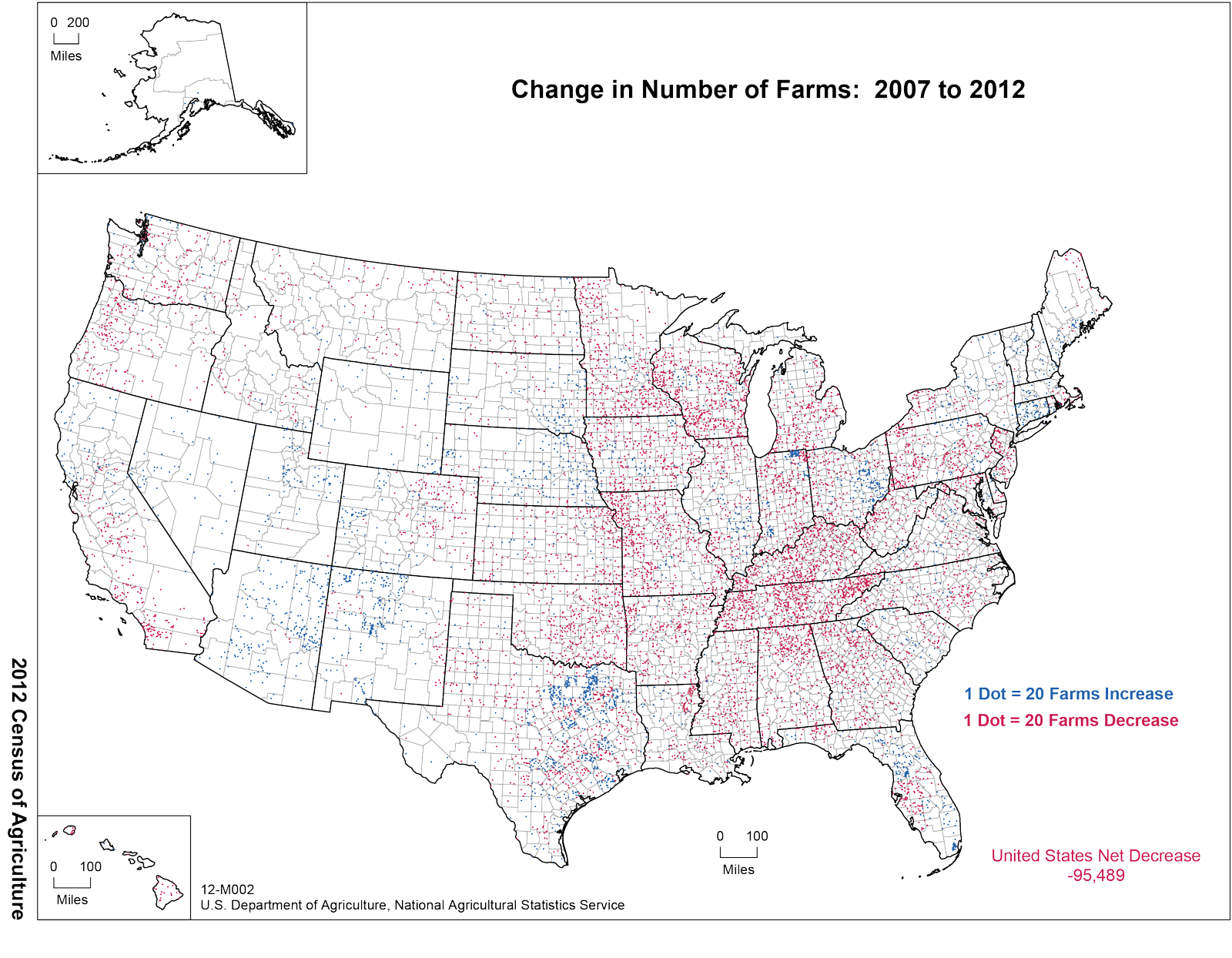

Not surprisingly then, average farm size is greater in the states that produce more field crops. Rural sociologists, agricultural economists, and farm advocates have long been concerned about the so-called “disappearing middle” in agriculture. While the amount of agricultural land has remained steady, the number of mid-sized farmers have declined precipitously.

For instance, while farmed acreage increased in Ohio from 1965 to 2014, the number of farmers actually decreased from 124,000 to 74,500 during the same period. Since the 1990s, however, small farms of less than 50 acres have grown as a percent of agricultural production—encompassing 39 percent nationally as of 2012. Farms of between 50 and 150 acres have slowly disappeared, generally taken over by larger operations.

Larger acreages generally mean more capital-intensive production systems. As acreages grow, farmers are more tempted to grow monocrops in rotation, to plant using larger and heavier machinery, and to use more chemically-intensive fertilization and pest management initiatives. Additionally, a consolidation of ownership has meant that more farmers rent or own land that is far from where they live. Scholars have found that while farm size is not necessarily associated with soil conservation behavior, farmers are more likely to recognize the utility of conservation when they lived close to or on the farmed land and near the affected water sources.

The changes in farm size and the economics of farming relate to agricultural policy, which has favored corn, soybean and livestock production in the Great Lakes region in the early part of the 21st Century. In particular, efforts to encourage bioenergy development through ethanol fuel production during the early 2000s inflated corn prices due to government subsidies. This dramatically expanded national corn acreage, including in the Great Lakes states.

Creating the right conditions

Algae growth was a significant and recurring problem throughout the Great Lakes through much of the 20th Century, until the passage of the 1972 Clean Water Act which imposed water quality regulations on industry and municipalities. These regulations had a significant and positive impact on water quality in the Great Lakes by obligating treatment prior to release of discharges of wastewater from cities, towns, industries – so-called point source contaminant regulation.

Algae carpets the sluggish waters of Wisconsin's Fox River on the northward leg of its course toward Lake Winnebago in this photo from 1931. The Fox River, which eventually drains into Green Bay and Lake Michigan still suffers from toxic algal blooms.

Starting in the late 1980s, clean water activists and policy makers began voicing concerns about the impact of non-point source contaminants, which come off dispersed sites across the landscape. The primary example is agricultural pollution. Over time, different arms of federal government and state/provincial governments have attempted to provide incentives to farmers to reduce non-point source pollution. These have include payments to farmers to encourage that they not plant on erodible land and incentives to encourage soil conservation and minimization of runoff.

Scientists and activists increasingly tie the algae problem in Lake Erie during the second decade of the 2000s to two factors. First, agricultural policies and markets that favored corn production led to dramatic increases in the planted corn acreage. Second, confined animal feeding operations that house thousands of animals for dairy and meat production are estimated to be major contributors to phosphorus runoff.

With more than 90 million acres of land planted, corn is the leading US crop. Most corn grown in the US is used for biofuel, and over a third is used to feed livestock. Beef production also creates manure, which easily discharges phosphorus and nitrogen into the water system.

This interaction between land and agricultural nutrients combined with a slight warming trend due to climate change, making the perfect environment for algae growth. Lake Erie is specifically vulnerable because of its position as the shallowest and the lowest of the Great Lakes. It receives water from Lakes Huron and Michigan that may be carrying contaminants, and it has less volume water to heat, creating an ideal growing environment for algae.

The 2015 algal bloom in Lake Erie was the worst on record. Photo: NOAA CoastWatch

There is now considerable awareness about the role of agricultural runoff in water quality impairment and algae growth. As a reflection of political will on this issue, the states of Michigan and Ohio and the province of Ontario pledged to take action to reduce phosphorous runoff by 40% by 2030 to address harmful algal blooms affecting Lake Erie. Action by the states builds on the United States Federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), which adds to federal government farm conservation dollars designed to help farmers pay for the cost of taking agricultural land out of production to protect water quality. However, despite the pledges of additional state support, the Alliance for the Great Lakes argues that there has been a “troubling lack of progress” toward meeting the goal. Experts point out that there has been a two-fold increase in total dissolved phosphorous in the Lake Erie Watershed since 2000.

What can we do?

Changing the conditions that enable algal blooms requires rethinking our relationship with food production. We can no longer ignore the impacts our food decisions have on our land and water, nor can we simply prioritize the ability to grow more crops or eat more meat. Knowing the causes, and what's at stake, we can make smarter decisions to safeguard our future.

→ Keep Phosphorus on the Farm

Agriculture will need to adopt methods that keep phosphorus (whether in the form of chemical fertilizer or manure) on farm sites and feeding plants. This may well require more support for the organic, low-input, or subsistence agricultural methods – which some believe if done correctly are less likely to runoff nutrients and impair water quality. Conservation organizations now call on farmers to adopt the 4-Rs – “the Right Source of Nutrients at the Right Rate and Right Time in the Right Place” – in application of fertilizer.

Visit LakeErieAlgae.com for more information.

→ Eat Low-impact Food

Growing more corn has significant water quality impacts. Protecting our water requires shifting from the crops that need lots of inputs, like corn and meat from confinement operations, to other kinds of food. You can help change the food production system by buying from small, non-conventional producers using low-input or organic methods.

There is mounting evidence that a shift away from the conventional diets associated with big agriculture – especially beef – is better for our health and the environment, including for water quality. Many communities have embraced Meatless Mondays, which can be organized around supporting small, local food producers.

→ Press for Higher Standards

Insist that the farms whose runoff flows to your water use cover crops, new techniques for applying phosphorus, and rotating crop mixes. In particular encourage farmers around you to be certified as responsible stewards by programs like the 4-R Nutrient Stewardship Certification in Ohio or the Michigan Agriculture Environmental Assurance Program (MAEAP), which are designed to certify farmers for using practices that protect water quality and environmental quality.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories