Working with Nature

Do we work for our landscaping, or can our landscaping work for us?

❖

By Ken Freestone

6 min read

LANDSCAPING

Act Now

↓Closely cropped lawns are so common in the Great Lakes region, many of us hardly notice them. But their pervasiveness – and the way we maintain them – puts us all at risk.

The United States has an addiction to high-maintenance, low-value landscaping. Our addiction stems from several historic factors that continue into the present, but is mainly driven by social status and marketing. Like many addictions, the lawn fix puts our health at risk and introduces dangerous chemicals into our water and soil. But we can wean ourselves from this addiction and create outdoor spaces that help to repair our region.

A persistent illusion

The 1950s image of a nuclear family with a tidy and manicured lawn hangs over North America, even as values and the climate have changed considerably. While most North Americans embrace well-manicured and maintained landscapes and the perceived benefits to home-owners, there are numerous downsides to these practices.

Levittown, Pennsylvania, brought the concept of assembly-line construction to the American residential market. Photo: Levittown Public Library

The United States has a general standard for “curb appeal” for our residential and commercial properties. Many cities have “standards” for how their communities should look and even strict ordinances and rules (commonly called Noxious Weed Ordinances) that frame a “common” look and/or feel. In many communities citizens can actually be fined for non-compliance of Noxious-Weed.

Lyrics from the musical Little Shop of Horrors perfectly capture the dynamic:

“In a tract house that we share

He rakes and trims the grass

He loves to mow and weed

Somewhere that’s Green”

The war on weeds

After World War II, native plants that grew easily gained the name weeds, defined as ugly encroachers on a standardized landscape. As GIs returned home from war, mass housing was built in suburban settings that defined post-war life for white families. Whereas interior domestic spaces were assigned to women who were supposed to engage in ongoing battles with dirt , men’s battles transpired outside where their task focused on keeping any non-standard plant off a mowed green lawn.

Such domestic wars characterized thousands of homes with cookie-cutter footprints and one feature landscaping called Turf Grass. Newsletters addressed to all homeowners in these subdivisions stressed the importance of a neat, weed-free, closely-shorn lawn and provided lawn-care advice on how to reach this ideal. This was an easy sell for thousands of GIs trained to be neat and to obey.

Homeowner’s Guide - Levittown, PA, The State Museum of Pennsylvania

The strictest instructions in the Homeowner’s Guide referred to landscape maintenance. Some of the orders in the nine full pages on the subject of landscape dictated:

“the height of grass should be kept to about 1 ½ inches during all months except from June 15 to August 15”

“there is one way and only one way to water a lawn. Use an OVERHEAD SPRINKLER on one spot for a short time, then shift the sprinkler to another spot.”

Science and technology worked to arm the domestic warriors in the struggle over the landscape. Inventions like the powered rotary lawn mower, effective (if not safe) pesticides, the first weed-free grass seeds, combined fertilizers and pesticides , and spreaders that made application easy combined to make lawn care seem parallel to the Green Revolution taking place across the world.

Chemical weapons for everyone

The 1950s phrase ‘Better Living Through Chemistry’ encapsulates how outdoor spaces meant to promote health and play became saturated in petrochemicals. Following World War II, chemical companies synthesized new fertilizers and pesticides, often including chemicals discovered during weapons research. Pesticides were sprayed freely on farms, lawns, and in parks. Children would run up to the sprayers to be sprayed with these wonderful new chemicals.

A commonly used weed killer is 2,4-D. Developed by Dow Chemical in the 1940s, this herbicide is one of the two active ingredients in Agent Orange, the notorious Vietnam War defoliant. 2,4-D has been linked to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in humans, Canine Malignant Lymphoma in household dogs, and the risks of birth defects and neurologic damage in children.

1950s advertisement for DDT

At what cost?

Although it can be good to collaborate on a shared vision of aesthetics and order for our communities, the current standards are set by chemical and energy companies that see our backyards and outdoor spaces as markets for their products, irrespective of their impacts on our families and ecosystems.

Of course, walking on freshly mown grass, playing games with our kids, or having social gatherings in our yards can be joyful. Public parks with well maintained grass can offer a sense of openness and space, and there aren’t any better conditions for sports than turf grass. Grass can promote fun and play, but our grass addiction contributes toxins and pollution to our streams, rivers, lakes and aquifers, contaminating the vital fresh water that we need to survive.

Not only does the harvesting of grass compromise our water, but we waste a tremendous amount of water and other resources in growing it.

Using Water, Land, Time, Money, and Energy

9 million gallons of water are used daily for landscaping.

12,240 gallons of water are used on average per household each month for lawns.

40 million acres of turf grass exist in the lower 48 States – the single largest crop in the US.

70 hours are spent mowing lawns each year per household on average.

825 million hours are spent collectively per year mowing lawns.

$3,000 per acre/year are spent for commercial maintenance.

800 million gallons of gas are used annually to mow lawns.

Getting off grass

What are the challenges to maintaining current landscaping practices?

Among the largest contributing factors to water degradation and to the loss of clean potable water are the practices of fertilizing crops, including lawns. Although the largest contributor to water pollution is industrial agriculture, homeowners and other large turf users such as golf courses must also bear significant responsibility.

Mowing lawns right to the edge of waterways increases runoff carrying fertilizers and pesticides.

Looking at the numbers above, it's obvious that we spend a lot of time and resources (natural and financial) on a crop that has little to no return on investment. Some of the challenges we face in our addictions to our lawns are the convenient and habitual routines we grew up with, fear of peer pressure or being different than our neighbors and potentially violating local ordinances, and simple ignorance of the damage lawns and related activities cause.

But there many opportunities for changing our landscaping practices.

What can we do?

We have the opportunity to create healthier habitats and conditions for humans, animals and wildlife. Changing our landscaping practices can reduce fossil fuel use, improve flood management, and save money and time.

→ Move from Grass to Native Landscaping

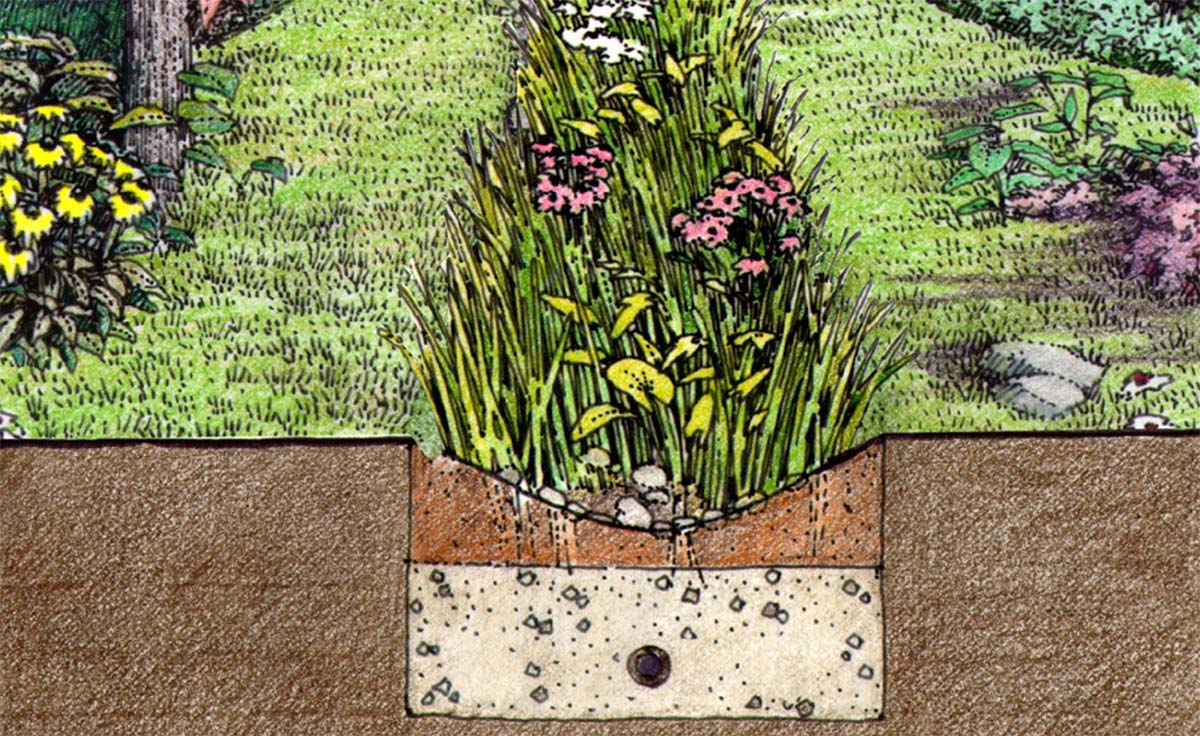

Low Impact Development (LID) is an easy way migrate towards healthier landscaping. It is simpler than most people think. With some basic pre-planning and design, effective low impact landscaping will yield natural beauty, benefits to nature and over many years, save money and time.

When a development is built in your community, such as a business, a school, or even your own home, hard surfaces such as pavement and roofs cause stormwater to flow more quickly to rivers and lakes and carry pollutants. LID is an approach to site design that helps protect our water resources by using techniques that absorb and filter stormwater. Improved water resources are an asset to property owners and the community. Plus, they make the community more attractive and can enhance property values.

→ Use the Landscape for Rain Capture and Filtration

Whether you live in an area prone to drought or one that experiences heavy rains, the outdoor spaces around you can help to hold and filter water. Turf grass has short roots that can’t hold water or replenish soil nutrients, but many plants can. Here are some guides to planting that enriches the soil and helps to live with healthy water.

Make your home, yard, and public areas Rain Ready.

Prevent flooding with a bioswale and prevent toxic runoff with smart design.

Vary the plants around you with a rain garden. Use public spaces to the benefit of the community’s water health.

→ Use Domestic Land for Small Scale Food Production

The Great Lakes basin produces significant amounts of agricultural goods and services. Michigan is second only to California in crop diversity. As the American West and Southwest experience increasing droughts and the Southeast suffers from increased hurricanes and sea level rise, our region is called upon to produce more food. However, if we continue to do so with heavy pesticide and fertilizer use, then we will contaminate our water sources and make conditions impossible for pollinating bees.

As a region, we’ve got to curb our use of chemicals on the soil and protect our water in the process. If we are wise and judicious about protecting our water resources, then we may be able to seize opportunities to grow more food and possibly create more jobs. By pioneering new modes of food production, and being stewards of clean water best practices, our region can become a global leader.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories