Building the Blue Economy

They’re not just for fishing — the Great Lakes create jobs and are America’s largest natural transit system.

❖

By Asher Kohn

8 min read

ECONOMY & JOBS

Act Now

↓Water drew people to the Great Lakes and stands at the heart of the region’s towns and cities.

The lakes and their rivers are the lifeblood of our economy, providing work for people in many different ways. But water is also a factor of inequality — large companies and their shareholders use water differently and have taken advantage of huge infrastructure plans to draw out more money than the smaller fish in the system.

Connecting the waters

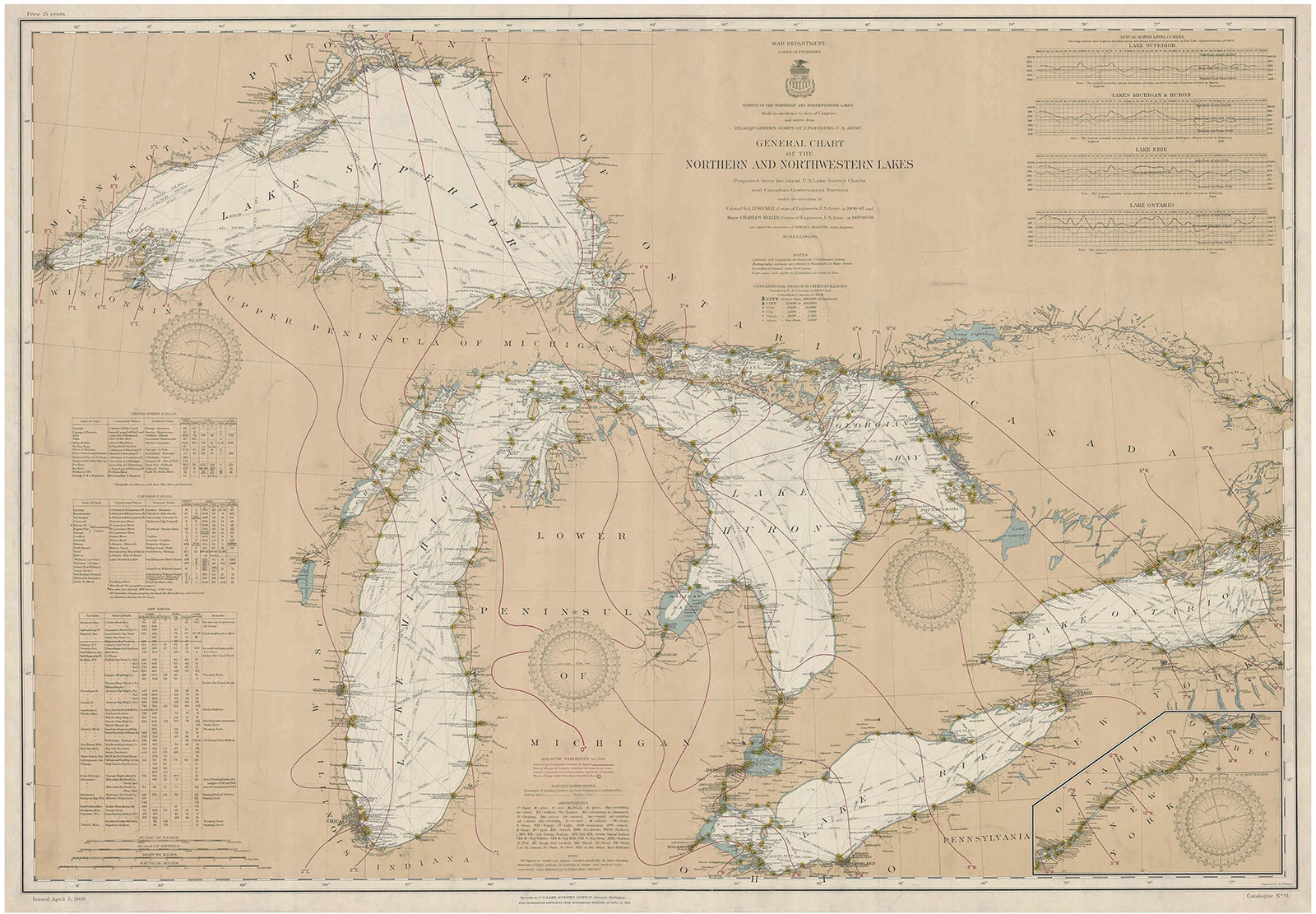

In the Midwest, the Great Lakes came first. The freshwater features were important for trade since their formation thousands of years ago. As late as the 19th century, maps of the region focused on water depths and narrow passages — not on the land where people lived along the shore.

Early mapping efforts focused on providing detailed nautical charts, like this one from 1909.

The Great Lakes Basin’s shared economy went through three major periods of expansion. The Erie Canal connected the eastern reaches to New York City in 1825 and the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal did the same in 1900, linking the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River, New Orleans and the Caribbean. The greatest growth came with the St. Lawrence Seaway, which allowed ocean-going tankers to ply the lakes upon its completion in 1959.

Commodities and landscapes

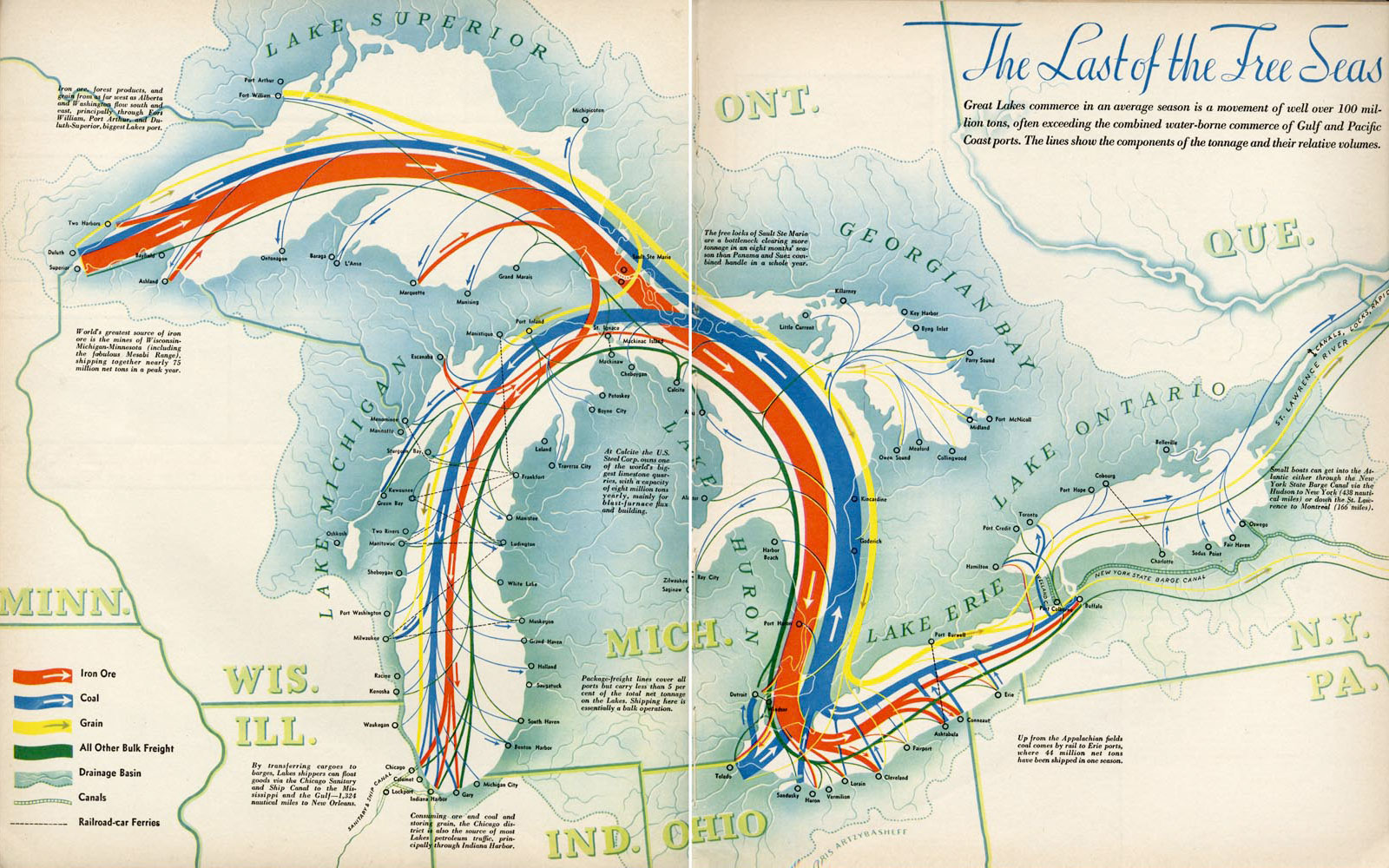

But why would corporations and governments spend millions of dollars every two generations in order to connect the Great Lakes with points outwards? In order to move valuable things in and out of the area. The grain of Minneapolis and Buffalo, the cars of Detroit and the lumber of Wisconsin were sold at enormous profits — much of which was stored in the region’s banks or went into building the skyscrapers of Chicago.

A 1940 map showing an overview of commodities trade throughout the Great Lakes.

People came from all over the world to work in the mills, factories and forests of the Great Lakes. They created cities, labor unions and remarkable restaurants. They also demanded clean water coming through democratically-owned infrastructure at a time when the great cities of Europe were purchasing from privately-owned companies like Veolia. As corporate executives and politicians profited by using the Great Lakes as a way to move goods around the world, the makers of these goods benefitted by using that water to grow grain, cool machinery and brew beer for drinking after a long day’s work.

Pollution in the “Rust Belt”

While the Saint Lawrence Seaway meant skyrocketing profits for some companies in the region, these companies neglected the water over which their commodities were shipped. Like the Erie Canal and the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, the Seaway compromised the Great Lakes themselves. Invasive species like Zebra Mussels arrived in the ballast water of oceanic ships, gorging on plankton and glomming on to freshwater infrastructure. Industrial corporations have downplayed environmental impacts of waste dumping, even as carcinogens show up in drinking water.

New political agreements changed the working landscape as the physical landscape degraded. A series of interstate bank laws and international trade agreements through the 1980s and 1990s made it easier for money to leave the Great Lakes and the country. Factories are expensive to maintain. Workers have high expectations. From a corporation’s perspective, the new bank and trade laws made it easier to construct factories elsewhere rather than bring workers to Great Lakes factories (and into Great Lakes unions).

The Gary Works steel mill in Gary, Indiana, was once the largest steel mill in the world, employing over 30,000 people at the time of this photo in 1973. By 2015, only 5000 jobs remained and the site was heavily polluted.

Less than 20 years after the Saint Lawrence Seaway opened up opportunities for Great Lakes manufacturers, factory-based employment began a steep decline. This was linked to a collapse in wages and a greater bifurcation between those who used water as an asset in white-collar employment and those who used water as an input in blue-collar work. Those who controlled what travelled on the water – what goods came in and out, and how – were able to sustain a high quality of life. Those who made things that went out and purchased what came in were not so fortunate.

A dry future?

The current Great Lakes economy, and its relationship with water, can perhaps best be glimpsed in the case of Flint, Michigan. There, a decision to move factory jobs away from the predominantly-Black city led to a decline in population and household income. This meant fewer sources of city revenue and cuts in infrastructure spending.

In addition, the State of Michigan reduced the amount of tax revenue that it shared with the City of Flint. These forces culminated in a complicated privatization scheme. The city’s water infrastructure was partially privatized in a deal involving the French corporation Veolia. The acts that led to the Flint water crisis stand in stark contrast to the public water works upon which the Great Lakes economy was built.

Fewer jobs and less-wealthy cities can lead to water degradation. This can create health crises – as it did in Flint – as well as a drying up of economic opportunities. It is not just Flint, after all: Veolia alone also has contracts in Buffalo, N.Y; Dayton, Ohio; and Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Good jobs and good water are intertwined, and there is a worry that good water will be in short supply in the coming decades.

Alternative visions

On the other hand, the Great Lakes region has been on the cutting edge of the economy before and it can be again. There is a push at local, state and federal levels for “green collar” jobs — a catchall term for expanding jobs like plumbing and construction into renewable energy industries.

Many cities are taking active roles in creating jobs that will help remediate water quality in their localities. Chicago, for example, is investing in the creation and maintenance of rainwater retention systems on vacant city-owned lots.

Tim Wilkins prepares to harvest lettuce at Cleveland's Evergreen Cooperative. Photo by Rick Wood / Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

Few Great Lakes municipalities have Chicago’s income base. In Cleveland, an ambitious cooperative workplace model was formed by local activists and large nongovernmental institutions. The Evergreen Cooperative Initiatives include a set of worker-owned sustainable businesses (such as an industrial laundry and an urban farm) which have a customer base in the city’s major employers: a local university, hospitals and the municipal government.

A “co-op” system like Cleveland’s gives workers a share in the ownership over the use of water, but what about ownership of water as an asset? The massive infrastructure projects of 1825, 1900 and 1959 were part of the industrialization of work and water in the United States. More giant projects won’t necessarily offer more work – and will almost certainly degrade water even further. A thriving 21st century economy must revolve around water stewardship in order to sustain a workforce.

Today, public parks and other municipal systems in the Great Lakes are taking the lead in innovating the water economy. They are the ones providing water to promote job creation and transportation — not the private companies looking for shareholder profit. Public systems may be the future, but only with citizen engagement.

What can we do?

For most of us, it takes a moment to realize how water courses through our personal lives. The first step of taking ownership of the water economy is to understand your role in it.

→ Drink Local

Bottled water brands like Aquafina and Dasani simply filter Detroit tap water. Nestle’s Ice Mountain brand extracts water from a Lake Michigan tributary, paying only $200 to pump millions of gallons of water a year. These megabrands deprive locals of the chance to develop a beverage industry with new forms of packaging that won’t end up in overflowing landfills.

Stick with your local tap water, filtering it to improve its taste and safety. Drink beer from your water source, giving local brewers your business. Or invent your own beverages, filters, and water recycling systems that can be made in your area.

→ Support Water Affordability Plans

The water economy plays a role where you live. Clean pipes and ready service are part of what keeps home values high in some areas — and poor water makes it difficult to use homes to build equity in others. Even renters’ monthly payments go into the upkeep of the pipes and the drains. Learn about one example, the Water Affordability Plan negotiated by We the People of Detroit and city officials. For more like this and more information on avenues of activism, visit the Water Equity Clearinghouse hosted by the US Water Alliance.

→ Join the Retrofit Economy

Much of our common, as well as our domestic, infrastructure is old and in need of updates. When you undertake projects in your home or business or advocate for larger civic projects, make sure to buy from manufactures that employ local workers and strive to safeguard their watersheds. You can find local manufacturers on the building clean website.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories