The Pipelines Among Us

The circulation of oil creates a network of relationships, not an irreconcilable divide between jobs and the environment.

❖

By Rachel Havrelock

7 min read

FOSSIL FUELS

Act Now

↓We interact with various forms of petroleum every day, and yet oil is something that we rarely see.

It usually only comes into view during a spill or leak, when oil gushes from pipelines or tankers into our waters. But knowing about the pipelines beneath our feet lets us make decisions about the tradeoffs between energy supply and safe drinking water before a disaster happens.

Do you know the sources of your oil?

If you live in the Great Lakes region, then your energy supply likely comes from Canadian Tar Sands mined in Alberta, Canada. Tar Sands are a kind of extreme oil, meaning that they cannot be pumped to the surface in their natural state. Instead, they must be mined, which destroys ancient boreal forests and unleashes carcinogens on nearby communities.

Alberta Tar Sands. Photo: Kris Krüg

As their name implies, the Tar Sands have a molasses (or tar) like consistency. In order to liquefy and move these sands through thousands of miles of pipelines the companies add chemicals called diluents. Because Tar Sands are made mostly of bitumen that can only move with diluents, the added chemicals are known as "dilbit." No one outside of the Tar Sands industry knows exactly what chemicals are in "dilbit," leaving people unsure of what exactly they need to clean up after a spill.

Does your oil cross water?

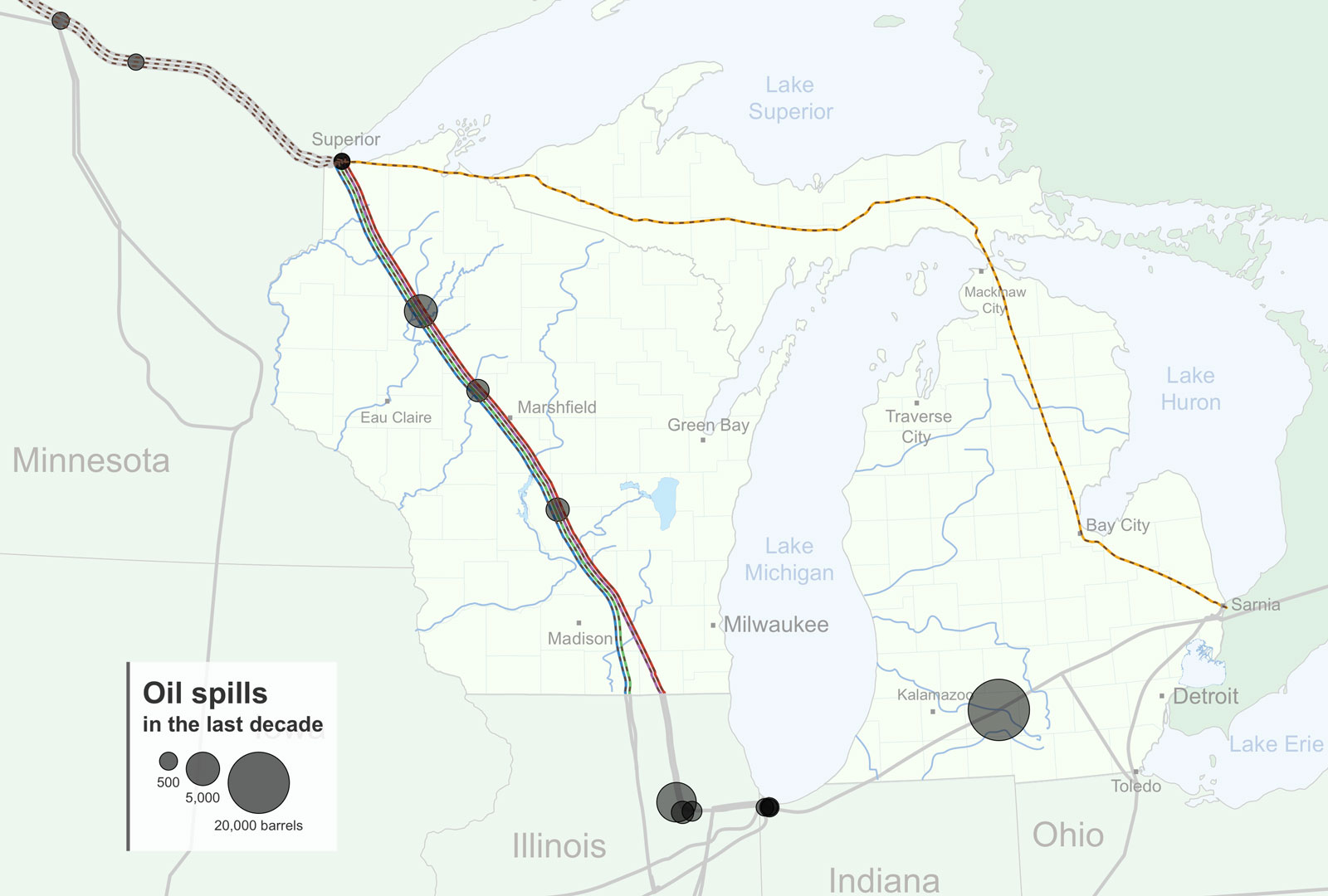

Run by the Enbridge Corporation, Tar Sands pipelines traverse many lakes, rivers, and wetlands. Most people don’t know that pipelines run along and across the Great Lakes, which contain 21% of the world’s fresh water and provide drinking water for 48 million people. Pipelines touch and convey refinery waste into Lake Superior at Superior, Wisconsin; Lake Michigan at Whiting, Indiana; Lake Huron at Detroit, Michigan and Sarnia, Ontario; Lake Erie at the Nanticoke Refinery in Ontario.

A map of the Enbridge pipeline system in the Great Lakes, showing recent oil spills. Source: Oil and Water

Of utmost concern is the sixty-four-year-old Line 5 pipeline lying on the bottom of the Straits of Mackinac where Lakes Michigan and Huron meet and exchange their waters. The two pipes that make up Line 5 convey 23 million gallons of oil a day across the Straits of Mackinac. Built to last for fifty years, the Line 5 pipe appears to be eroding and is missing many of the mounts required to hold the pipeline in place.

Studies have projected that a breach of Line 5 would spread its contents 722 miles and into the drinking water of communities across the shores of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron.

Kalamazoo River spill

In 2010, Enbridge Line 6b that runs from Griffith, Indiana to Sarnia, Ontario ruptured, pouring close to a million gallons of diluted Tar Sands into Talmage Creek, which feeds the Kalamazoo River and ultimately Lake Michigan.

A view of the Kalamzoo River spill in 2010

This largest inland oil spill into fresh water was overshadowed by the Deepwater Horizon rig blowout in the Gulf of Mexico during the same summer.

But nothing changed following this summer of spills. In Michigan, the reconstruction of the 6b pipeline became the occasion for Enbridge to increase its size and capacity.

Oil in the wind

Photo: Terry Evans

Petroleum Coke or petcoke is a type of coal produced as a byproduct of Tar Sands refining. It is so toxic when burned that it's illegal to use petcoke in the United States. Yet petcoke is produced in Great Lakes cities and sold to other countries by American companies.

After it's pressed into coal, petcoke contains tiny particles that come apart in the wind. In August 2014, a storm of black dust coated a Chicago little league field. The game was called and the petcoke storm led residents to question its source. Neighborhood leaders discovered that prolonged exposure to petcoke causes respiratory illnesses, heart disease, and cancer. Community groups in Chicago, Northwest Indiana, and Detroit successfully lobbied for petcoke to be stored in closed structures instead of open piles.

Petcoke under a roof is certainly better than open pile storage, but it's not a guarantee of safety, and it only applies to storage on land; petcoke is still exposed on barges sailing through rivers and lakes. The very processing of the dirtiest form of energy puts the water and air of everyone in proximity to a facility or barge at risk.

Unfortunately solving the problem of petcoke isn't as simple as stopping its production. Like coal, the very people who most suffer from its effects often work in the industry, producing and transporting petcoke through their own neighborhoods. In many places these are the only jobs available, and residents have little choice but to put their families at risk. Any long-term solution will need to support these communities in changing their environment and livelihood at the same time.

What can we do?

While many of the problems of oil production and distribution are structural, there are concrete steps we can take as individuals.

→ Pull Line 5

Local residents and drinkers of Great Lakes water have called for Line 5 to be decommissioned and pulled out of the water. The risk of a disasterous spill and the lack of transparency on the pipeline's safety is a troubling mix. You can join the call to pull the pipeline.

→ Demand A Just Transition

We can no longer separate the work that we do from the lives that we lead. Our working lives directly impact our long-term health and the safety of our communities.

We can all demand that industry and agriculture curb practices that impair our shared waters. In the case of Tar Sands refining, frontline communities have firsthand knowledge of the dangers and health risks. We can support them by advocating for water quality monitoring by refineries and by working collectively for a just transition to a renewable energy economy.

With fossil fuel prices down and jobs reduced through automation, now is the perfect time to pursue a 21st century renewable economy. Learn more about this movement from the Our Power campaign.

→ Own Your Energy

New wells and new pipelines are being commissioned all the time. Learn how to engage in the energy discussions in your community.

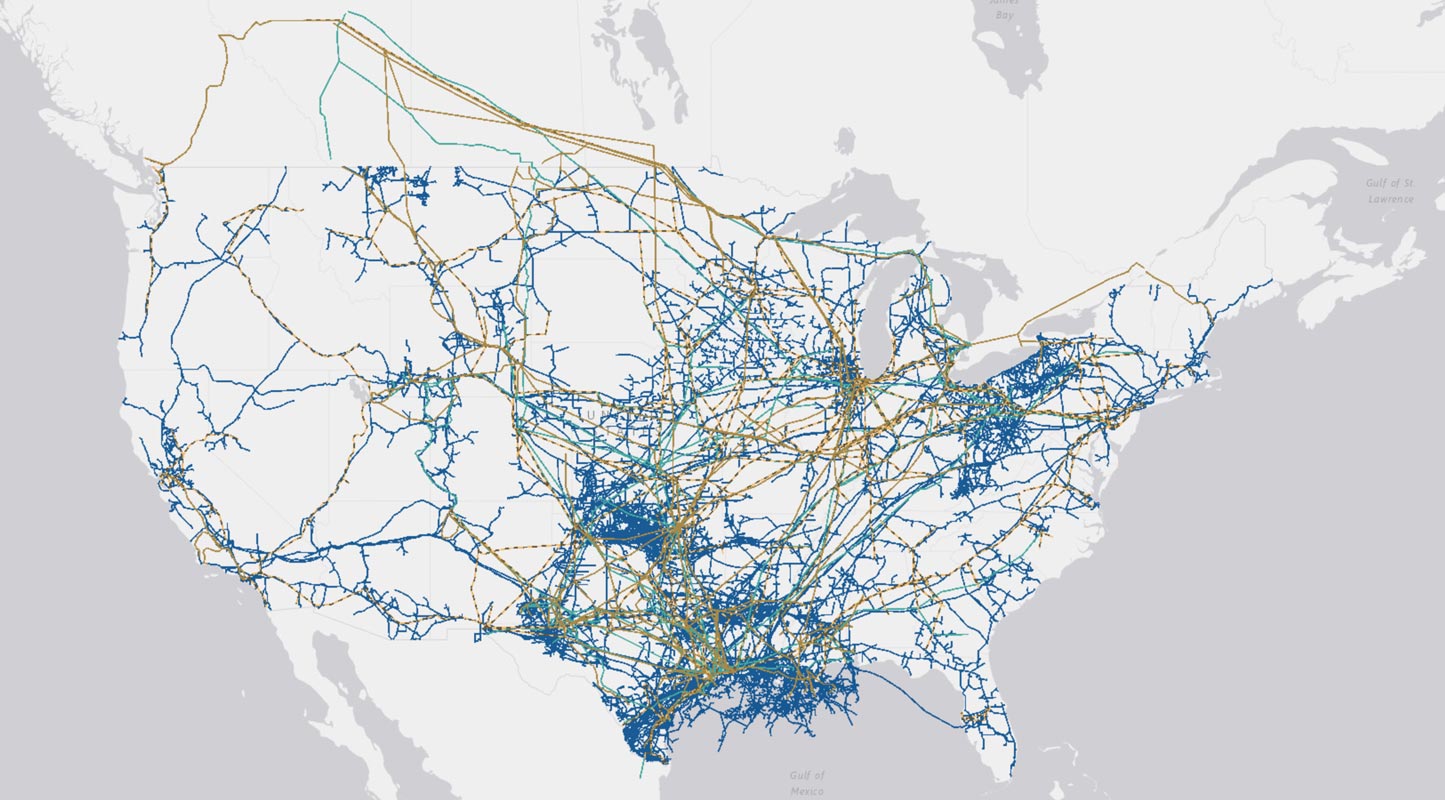

As a step toward becoming more involved, find your closest pipeline. With over a million miles of pipelines across the U.S. and a network a pipes all over the world, chances are you live near a significant pipeline. Learn about some of the most watched fossil fuel projects on the horizon.

In addition to pipelines, much of the crude oil in North America travels by rail. Find out if a railway near you is carrying oil with this interactive map.

What part of the fossil fuel economy presents the greatest risk to your community? What is the risk to your watershed? Who is responsible for its safety?

The shift from corporate generated fossil fuel energy to renewable energy can move us from an individual consumption model to a system of jointly-owned, distributed energy networks. Learn more about Community Solar Models.

Make Your Voice Heard

Most local government offices hold public meetings on proposed projects or accept public comments for a period of time. When making public comments on a comissioned report or proposed plan, consider the following:

- Clarity: Are any parts of the report confusing and need clarification?

- Data: Are there any sources of information that should have been included that were not?

- Completeness: Upon review of the report, did the contractor fail to cover a key topic? If something was left out, was the reason for doing so addressed and is the reasoning sufficient for the exclusion?

- Methodology: Was the methodology understandable or does more information need to be given? Is it sufficient to accurately address the questions presented? Are there any flaws in the methodology used?

- Cost: Are all cost components identified, or is there a category of costs that were not considered?

- Report Assumptions: Are the assumptions in the report realistic? Are they explained well?

Want to reach a larger audience? Share your views on fossil fuels and water security by writing an op-ed in your local newspaper.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories