What's in the Water?

Pipes, drains, drugs, and money link us to our water systems in sometimes subtle ways.

❖

By Tim Oravec

8 min read

DRINKING WATER

Act Now

↓We’re all familiar with the nutrition labels on the sides of boxes, bottles, cans, and bags we bring home from the grocery store.

They’re so ubiquitous that we sometimes forget these labels save lives. Imagine going to the grocery store each week as the parent of a child with a severe allergy to peanuts or gluten, but not having labels to let you know what’s inside the food you buy.

What if there were a similar label on the side of each glass of water you drink, telling you exactly what’s inside—the good, the bad, and the ugly? Would you be brave enough to look?

The rise of clean water laws

The United States Congress passed the Clean Water Act in 1972 and the Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974. These statutes established stringent regulations for discharges into our shared waterways and standards for systems that provide drinking water to millions of Americans every day. Their impact cannot be overstated.

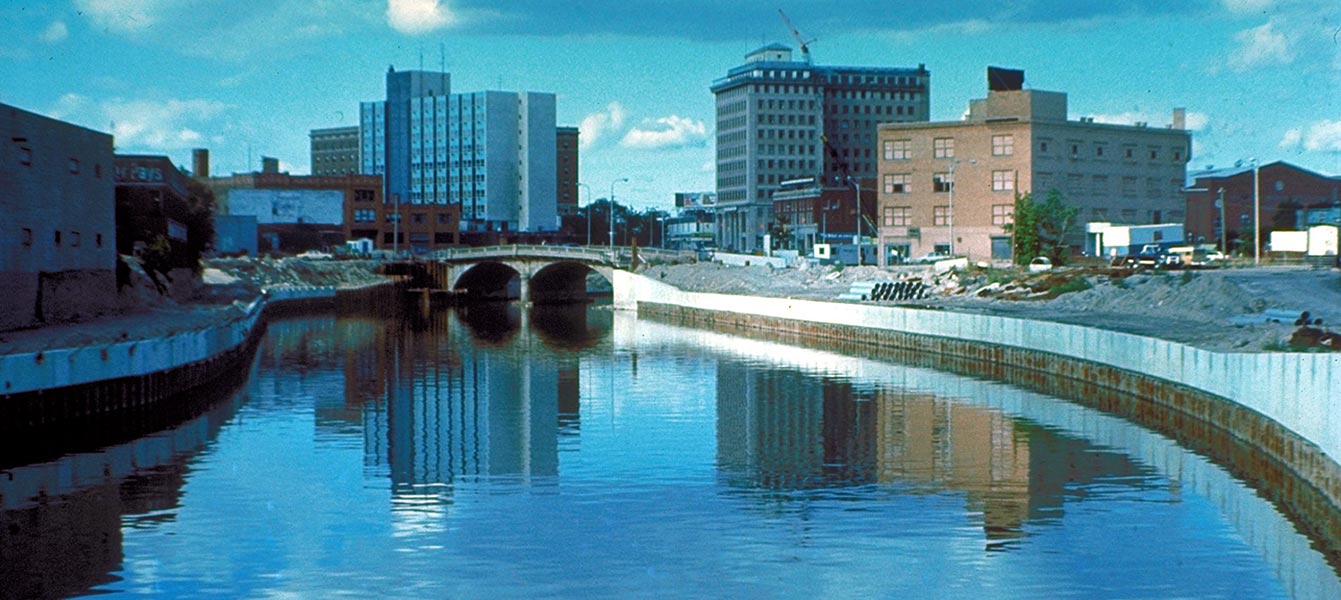

Decades ago many rivers and lakes were often the site of dumping, like this scene in Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana.

Before passage of these laws, individuals and companies could pollute waterways liberally and without consequence. Lakes and rivers became so contaminated that fish would be found floating listlessly on the surface, killed by the toxic brew infiltrating their habitat. The Cuyahoga River in Ohio was so polluted that it actually caught on fire in 1969. Drinking water often underwent little or no standardized testing to ensure that it was safe. But after these laws passed, the health of lakes, rivers, and streams began to improve across the nation, and United States citizens could begin to rely on their public utilities to ensure that drinking water was tested, source water protected, and information provided whenever water quality fell short of federally-set standards. Environmental and public health improved.

But try telling that to the residents of Flint, Michigan, who learned that there was so much lead flowing through the city’s drinking water, and showing up in residents’ blood, that Mayor Karen Weaver declared a state of emergency. Try telling that to the residents of Crestwood, Illinois, who learned in 2009 that their municipal officials had been lying to them for nearly two decades by claiming that the drinking water was perfectly safe, knowing all the while that it contained cancer-causing chemicals. Tell that to the residents of Kewaunee County, Wisconsin, where state-funded tests found more than 30 percent of drinking water wells with unsafe levels of e. coli, nitrates, and fecal bacteria.

If the United States has some of the best federal policies for managing water quality, why are we facing so many problems with our drinking water?

Making our own fate

Drinking water crises, unlike major natural disasters, are not entirely beyond the control of humans. In fact, it’s likely that most drinking water crises are the consequence of human choices and behaviors.

Consider both Flint and Crestwood. Decision makers behind the crises in Flint and Crestwood did not expose residents to unsafe drinking water because they wanted to harm those residents; instead, it was because they wanted to save money. The distinction in no way absolves them of blame, or in any way justifies their actions. Ignoring serious concerns about the safety of drinking water is a grave and unforgivable abuse of power. But it must be understood that drinking water problems are often about more than just learning that something threatening is in the water—they’re also about governance, policy priorities, politics, and real economic concerns that sometimes pressure public officials to make terrible decisions.

Problems arose when Flint, MI changed its source of drinking water to the Flint River.

Money may not be the root of all evil, but there’s no question that it played an outsize role in Flint and Crestwood. Flint’s lead crisis may have been avoided had Michigan officials not switched the city’s water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River’s less expensive, albeit far more corrosive, water. Indeed, the new water source was so corrosive that it ate away at the lead service pipes, exposing residents to irreversible harm. Crestwood’s officials decided that tapping into a highly contaminated well, without residents’ knowledge, would save them more money than repairing the water mains that normally provided safe water from Lake Michigan.

Repairing and replacing the country’s rapidly aging water infrastructure requires enormous amounts of capital, and many municipalities simply don't have resources available to invest in infrastructure upgrades without sacrificing other services. Elected officials know that asking residents to increase their taxes to pay for costly infrastructure improvements can be an incredibly tough sell.

Of course the public should expect officials to do what’s right even when it’s not easy, but it would be naïve to assume that there won’t be more drinking water crises like those in Flint and Crestwood if the economic and infrastructure challenges that allow them to form are not also addressed.

So, would drinking water problems be solved if municipalities just increased funding for infrastructure and water quality projects?

Down the drain, into the cup

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. Policymakers are increasingly concerned about what they call emerging contaminants, or chemicals that scientists have only recently begun to discover in the water environment, and are therefore uncertain about possible threats they pose to humans and the environment. Because so little is known about these contaminants, they often go unregulated and unmonitored. How can you manage a problem you don’t fully understand?

Emerging contaminants include, to name a few, microbeads from exfoliating soaps and lotions; pesticides and herbicides used for residential lawn maintenance; artificial sweeteners added to many popular beverages; and flame retardants that wash away from fire-proof fabrics.

Most water treatment facilities were not designed to handle pharmaceuticals and other emerging contaminants.

One class of emerging contaminants that has stirred up considerable consternation is pharmaceuticals. Why? It turns out that many people dispose of their unwanted or expired drugs by flushing them down the toilet or sink. What many people don’t realize, however, is that wastewater treatment plants are not designed to completely remove pharmaceuticals; instead, they break down to concentrations so small that they pass through and enter rivers and streams with treated water, called effluent, discharged from the plant. Studies across the nation are finding fish, frogs, oysters and other aquatic critters with altered reproductive organs and hormones—and a cocktail of pharmaceuticals in their bloodstreams. Scientists know that pharmaceuticals are having disastrous effects on aquatic ecosystems, and that miniscule traces of pharmaceuticals have been found in some drinking water supplies, but nobody knows what effect they might have on human health.

What about bottled water?

Americans are hooked on bottled water. Last year, sales of bottled water surpassed those of soda for the first time, becoming the most popular purchased beverage in the United States. Yet despite the popularity, slick marketing, and heightened awareness about tap water quality, you may want to think twice before buying into the bottled water craze.

First, consider the cost. Gallon for gallon, tap water is much cheaper. The American Water Works Association found that a gallon of tap water costs, on average, about $0.0004. That’s about three hundred times less than the price for a gallon of bottled water.

And don’t assume that a higher price means better quality. Many bottled water companies source their water directly from the tap (if the bottle says that it comes from a “community” or “municipal” source, that’s usually a dead giveaway). According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, most bottled water undergoes less frequent testing and is not required to meet the same safety standards as tap water. There are also concerns about the bottles themselves, specifically hormone-disrupting chemicals called phthalates used to produce the bottles, caps, and liners that may leach into the water. Finally, bottled water lacks transparency. While publicly-owned water utilities are required to inform residents about the source of their water and what is in the water they’re consuming, bottled water companies generally are not required to disclose any information on its quality, source, or treatment process.

Then there’s the bigger question of ownership. Water is essential for all living things. Humans can go weeks without food, but only a few days without water. People congregate to form communities and cities around shared water resources. The assumption that we will have perpetual access to clean, affordable water underscores every aspect of our lives. Doesn’t it make sense, then, that something so critical to our survival should remain controlled by the public? Think about it: When we purchase bottled water, we support private companies that draw enormous amounts of water (sometimes for free) out from aquifers, rivers, and lakes, package it in plastic containers, and then sell it back to us for a profit. The public has no control over how these companies operate, no access to their bottling and treatment procedures, and no stake in the profit margins. If water is to remain a human right, it must also remain within the public’s control. Bottled water slowly chips away at that control.

What can we do?

When threats to safe, clean drinking water are so systemic and difficult to understand, how can an individual citizen help ensure that the water they drink is safe?

→ Read the Labels

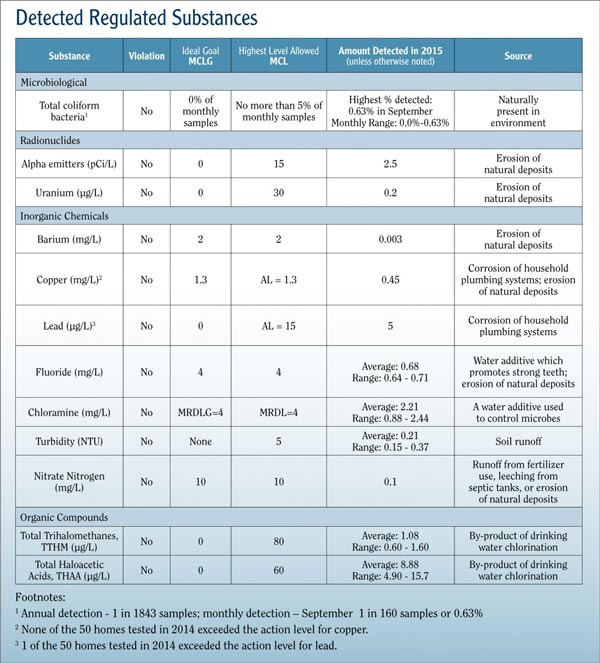

A water quality report includes information on contaminants and their sources.

First, read the labels. Just like you check labels on the food you purchase, you should make a habit out of reviewing your municipality’s annual consumer confidence report that details the results of water quality testing throughout the year. Many municipalities make these available online and mail them to residents. If you can’t find your municipality’s water quality consumer confidence report, give your local officials a phone call and ask them to send you one in the mail.

You can also consult the Environmental Working Group’s national tap water database at www.ewg.org/tapwater. Simply enter your zip code, choose your municipality, and the database will provide information about contaminants detected by your water utility, how those concentrations compare with national averages, potential sources of contaminants, tips for filtering your water, and other useful information.

Information about the source and quality of bottled water isn’t as accessible, but there are resources available for the curious consumer. Many water bottles include phone numbers and addresses on the labels or packaging where you can direct questions. Ask to receive copies of results from recent water quality testing, whether tests are conducted in-house or in third-part laboratories, what water source is used (not just the general packaging location), how the water is treated, and information about any recent product recalls.

→ Become Drain-Sane

Second, and this may be the most important, is to always ask yourself if you’d be comfortable finding out whatever you send down the drain is also coming out of the tap. Pharmaceuticals, household chemicals, pain medicines, bleach, and products containing microplastics should never go down the drain because they can end up in the water supply, harming wildlife and—potentially—humans. If you’ve ever poured these down the drain, there’s a good chance your neighbors have too. Share with them what you learn about appropriate disposal of products that could harm drinking water, and work together to ask your municipal government to support opportunities for residents to dispose of these products safely.

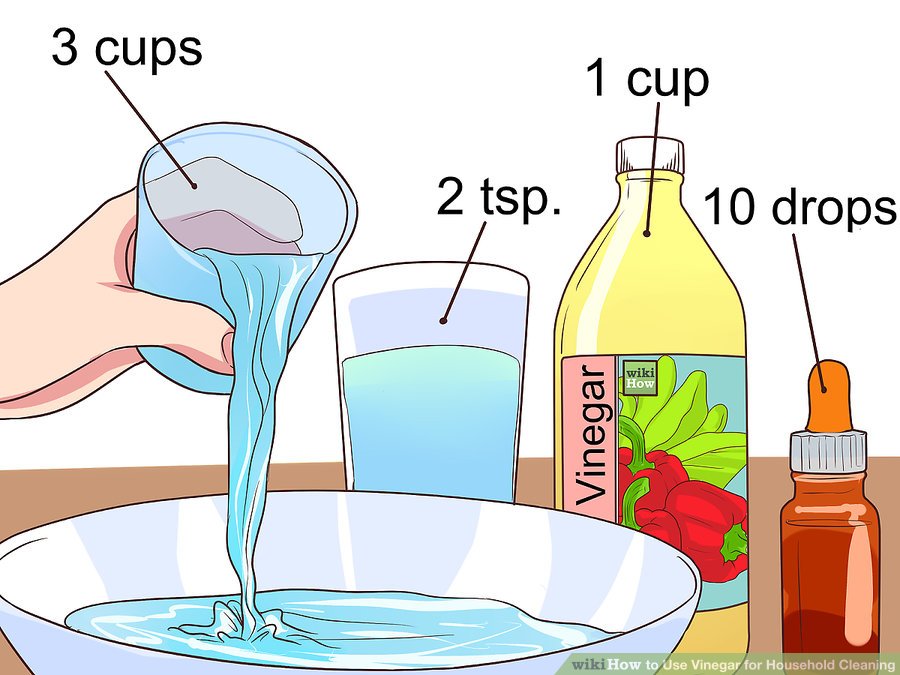

Clean without chemicals

Did you know that vinegar can be used to clean almost anything in your home? It's non-toxic, inexpensive, and can be poured down drains safely. Simply mix equal parts water and vinegar and put it in a spray bottle for a homemade disinfectant, or try one of our favorite general purpose cleaning solutions:

- 3 cups (705 ml) of water

- 1 cup (235 ml) of vinegar

- 2 teaspoons (10 ml) of lemon juice

- 10 drops of lemon essential oil

Find more vinegar-based cleaning solutions for everything from mattresses to clogged drains.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories