Minerals and the Social License to Operate

When local communities overwhelmingly reject extractive projects that risk their health and way of life, who listens?

❖

By Burton W. Warrington

7 min read

MINING

Act Now

↓We like to think that when it comes to companies operating on shared land, our voices matter. But is that really true?

This question hangs over the dangerous open-pit sulfide mine called The Back Forty Mine. A wide range of people from across the political spectrum reject the mine, yet its sponsor, Aquila Resources, Inc., continues to dismiss public opposition in their desire to blast trace amounts of lead, gold, silver, zinc and copper out of sulfide rock on the banks of the Menominee River. If stakeholders are overwhelmingly united in their opposition, why are they being ignored?

A terrible plan

The proposed Back Forty Mine aims to leech metals out of rock by blasting open the ground and adding harmful chemicals, creating sulfuric acid waste. The location of the mine is just 50 yards from the Menominee River that feeds Green Bay and is a major tributary of Lake Michigan. Beyond the damage to the river, the mining chemicals could end up in the water of everyone who drinks from Lake Michigan. The surrounding aquaculture, ecosystem, and wildlife habitat are all imperiled by the mine.

Take some time to let this information sink in. Mining is known to be the most destructive industry in the world. Aquila Resources, a Canadian exploratory company that has never opened or operated a mine, expects residents, business owners, and workers in Michigan and Wisconsin to trust them blindly. As of the fall of 2017, Aquila has been granted three of the four permits required to move forward with the project.

An open pit copper mine in Australia, similar to the one proposed at the Back Forty site.

The overall project property is 580 acres with the proposed open pit measuring 2,000 feet by 2,500 feet and 750 feet deep. In addition to the open pit mine, Aquila is proposing to build an onsite plant to process the gold, silver, copper, zinc and lead. While the company gives the shorter date of seven years to local residents and permitting agencies, it pitches a sixteen year mine with an open pit and an underground component to investors.

Local stakeholders who would be most impacted by the mine have been persistent in their opposition. The company likes to say that their opponents are ‘just’ liberal environmental protesters. They couldn’t be more wrong. Donald Trump won six of the seven counties opposed to the mine, including four by more than 60 percent. Despite attempts to make this a partisan issue, it is not. This is a water issue that impacts everyone who drinks from the Great Lakes and hews to no political or ideological boundaries. It’s about threats to an entire region’s way of life, intrinsically tied to clean water. It’s about Republicans and Democrats alike, liberals and conservatives alike, who are not willing to accept the risks associated with the project.

The source of life

Following the high-profile resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock last year, people around the world have embraced the statement “Water is Life.” For the Menominee People “Water is Life” could not be more true. The story of human civilization on the Menominee River dates back thousands of years to the Menominee creation story. The story tells of the ancestral bear who emerged from the Menominee River and was transformed into human form as the first Menominee.

For thousands of years the Menominee people flourished on the banks of the Menominee River, but they knew their lives would change forever when Menominee dreamers foresaw the coming of a light skinned people in large boats. This prophesy came true in 1634 when the French explorer Jean Nicolet arrived at Green Bay. Through a series of treaties, the Menominee Nation was pushed into a reservation about 40 miles from the sacred river of their origin.

The Menominee River in the fall. Photo: Tom Young.

Today, the mouth of the Menominee River is the home to the sister cities of Marinette, Wisconsin and Menominee, Michigan. One of the largest watersheds in the region, the Menominee River serves as the border between Northern Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Much has changed since 1634, but, despite all the change, the Menominee River remains one of the most serene and naturally beautiful areas in the Great Lakes. Many retirees, multigenerational families, vacationers, sportsmen and sportswomen, and area residents rely on the natural beauty and the majestic powers of the Menominee River as an escape from hectic city life. But contemporary struggles came to the river when the Back Forty deposit was discovered in 2001.

Pollution that can't be stopped

Metal mining is the nation’s number one toxic polluter. Most modern ore is extremely low grade, meaning that the small concentration of the valuable metals are embedded into rock, such as sulfide rock at the Back Forty deposit. To get to the small content of valuable metals, mining creates huge amounts of waste rock. For example, the average gold ring generates more than 20 tons of waste. So much metal already exists in processed form that we can easily get the substances we need by repurposing older objects. A reuse economy relies on human creativity and ingenuity much more that blasting rock and pouring poisonous chemicals into water.

When sulfides in rock are exposed to water and air, sulfuric acid is created, which leads to acid mine drainage. Once acid mine drainage begins, there is no way to turn it off. It can pollute water in perpetuity. Roman Era mines have been discovered that still produce acid mine drainage.

The EPA estimates that 40% of the headwaters of western watersheds have been polluted by mining, particularly by acid mine drainage. According to government and company data, 40 existing mines in the United States alone will contaminate 17-27 billion gallons of water every year, forever. To this day, the mining industry cannot prove that they have technology that can ensure control of acid mine drainage. As proof of this all one has to do is cross over the Menominee River into Wisconsin, where for the last twenty years the mining industry has not been able meet the Wisconsin standard which requires companies to prove they can be operated safely.

The Flambeau Mine (a Kennecott/Rio Tinto project) operated on the banks of the Flambeau River near Ladysmith, Wisconsin in the mid-1990s. This photo was taken in 1994 when the river flooded during heavy rains and came within 20 horizontal feet and 4 vertical feet of spilling into the mine pit. Despite assurances from the company, toxic chemicals were found to have leaked into the groundwater and river. Photo: Bob Olsgard.

In researching fourteen operating U.S. Copper Mines (accounting for 89% of U.S. Copper production), Earthworks found that 100% had pipeline spills, 92% failed to control mine wastewater and 28% had tailing impoundment failures – polluting drinking water, destroying fish and wildlife habitat, harming agricultural land and threatening public health. Aside from the inherent and unavoidable risks associated with metallic mining, once the potential for natural catastrophes or human error are factored in, the risks are greatly enhanced.

The Animas River in Colorado before and after one million gallons of wastewater containing lead, arsenic, and cadmium leaked from a goldmine, turning more than 100 miles of the river orange.

So who is on the hook for cleanup? The history of the metallic mining industry is filled with companies going bankrupt or lacking the financial resources to respond to the pollution. Whether it’s the Summitville Gold Mine in Colorado, the Zortman Landusky Mine in Montana or the Gilt-Edge Mine in South Dakota, it’s not hard to find bankrupt companies who left the public with an unwanted gift that keeps on giving. The backlog of cleanup costs for hardrock mines in the U.S. are estimated to be between $20 and $45 billion.

What is a Social License to Operate?

A Social License to Operate (SLO) refers to the level of acceptance or approval by local communities and stakeholders. This concept is becoming increasingly more important as major industries and financial institutions embrace the broader concept of Corporate Social Responsibility. The SLO for the Back Forty project is not controlled or issued by the state or federal government, but rather by the stakeholders such as the local communities, local governments, indigenous peoples, non-government organizations and other interest groups.

EY (formerly Ernst and Young), one of the world’s largest professional services firms and one of the “Big Four” accounting firms, lists the SLO as the fourth biggest business risk for mining and metals in 2016-2017. The lack of a SLO can have devastating effects on a project, including lengthy and costly delays from legal challenges, higher financial costs, limited financing options, and increased difficulty in recruiting and retaining employees.

No jobs, no water, no future

Aquila Resources also likes to justify its plan by projecting large numbers of jobs, but Mining Magazine predicted that, in fact, The Robots Are Coming. In four open pit mines (and an underground mine) in Australia robotic excavators are digging the ore that driverless trucks move out of the mine to driverless locomotives in the processing cycle. Neighboring humans could be left without work or potable water.

In contrast, pure water in the Menominee River, Green Bay, and Lake Michigan can drive local food and beverage production, support manufacture of water filtration and reuse technologies and add to the value of property as many of the world’s water sources dry up or reach a state of contamination beyond repair.

Whose future matters? That of robots and global mining corporations, or the residents of communities along the river?

What can we do?

The mining industry may appear robust, but it actually involves enormous financial burdens and risks, making it highly vulnerable to pressure on investors and changing market conditions.

→ Defund the Back Forty Mine

As a development company, Aquila lacks a meaningful income stream. For the foreseeable future, they will be engaged in costly development activities. Thus the company routinely finds itself facing the daunting task of trying to convince investors to continue sinking more money into the speculative project. Based on the current status of the project, including existing and expected legal challenges, a lack of a social license to operate, a lack of a feasibility study and uncertainty over who has the authority for the wetland permit, ongoing fundraising efforts will face increasing scrutiny. Call on the three major firms investing in the project to withdraw their support.

Learn more about opposition to the Back Forty Mine at www.noback40.org.

→ Advocate for Metal Reuse

Reusing metals can eliminate the desire and financial incentives for new mines. Many towns and cities offer resource recovery as part of their recycling programs. Contact your local government to find out what metals are recycled in your area and how they are handled. Organize to pass a local ordinance to encourage recycled or recovered materials in local building projects.

The Institute for Local Government has developed resources to help implement commercial recycling, including a sample commercial recycling ordinance, a sample outreach and education flyer, examples of local commercial recycling programs and other resources to help local officials increase commercial recycling in their communities.

→ Demand a Lead Role for Residents

Local residents have the most at stake in mining projects, and they are becoming increasingly aware that the long-term risks of mining far outweigh the short-term benefits, especially when it comes to water. When we allow companies to open and run mines without a Social License to Operate, we silence those communities and condemn them to suffer for generations.

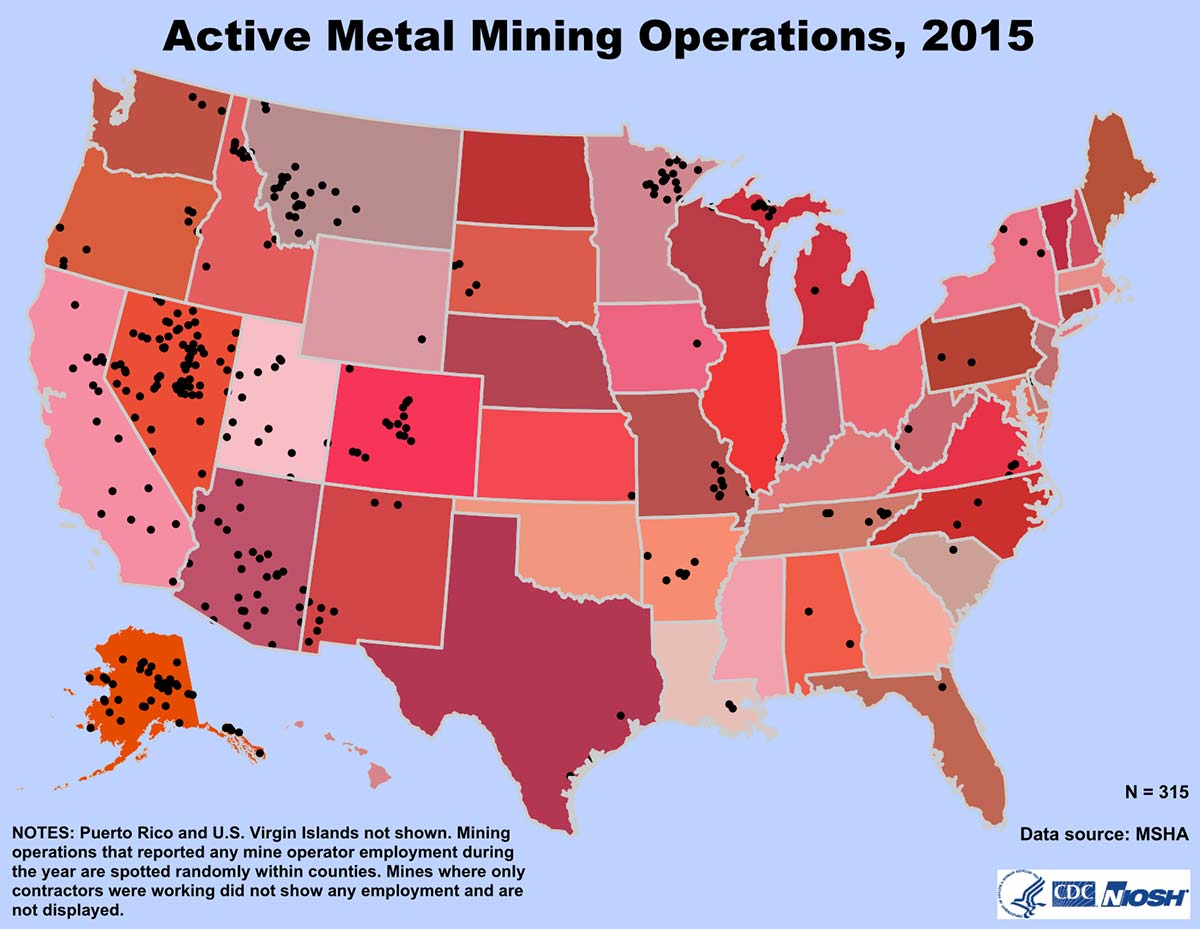

Find out what metal mines operate in your area, and talk with your friends and family about the long-lasting dangers inherent in mineral extraction.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories