People, Power, and Water

The communities experiencing water system failures are too often excluded from decisions that can determine their fate.

❖

By Antonio Lopez

7 min read

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

Act Now

↓Standing on the banks of the 31st Street Collateral Channel in the Little Village neighborhood of Chicago, you are immediately struck by a foul odor that emanates from the former industrial waterway some 15 feet below.

Once a part of a bustling industrial transit system, the channel is now one of the most toxic waterways in the entire city. Only steps away from a new park where children and families play, the toxic water is filled with parasitic worms and heavy metals. On hot days in the summer, the water actually bubbles and releases methane into the air.

I’ve given multiple toxic tours and taken journalists to see the 31st Street Collateral Channel up close. On one occasion the smell was so powerful that a local newspaper writer became visibly nauseated and we had to quickly leave the site. I often remind toxic tour participants that such experiences are unfortunately a daily reality for residents in frontline communities.

A legacy of neglect

Located in a low-income Latino community, the 31st street Collateral Channel is a prime example of environmental racism in the city of Chicago. Considering that the contamination of the water has remained for decades, we have to ask some direct questions:

Would this toxic waterway persist if the surrounding community were white and affluent?

Why has it taken so long for the City of Chicago and Metropolitan Water Reclamation district to address an issue that community members have raised for a number of years?

Why would local politicians and decision makers not be alarmed that a toxic and harmful waterway exists in the community and work urgently to at least fence off the area?

A closer view of the 31st Street Collateral Channel's toxic waters.

These questions are asked all the time by the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) and other environmental justice organizers across Chicago and the Great Lakes Basin. Indeed, despite having deep community expertise, years of experience, and long track records of successful organizing, frontline perspectives and organizations continue to be marginalized by decision makers, researchers, and even within the environmental conservation movement. Though these communities are the most burdened by environmental hazards and have the most at stake in environmental policy, they are often excluded altogether from decision making or exploited for their outreach efforts.

Frontline communities already have the solutions

Fortunately, community leaders across the region are not waiting for support from mainstream environmental organizations. In recent years, a dynamic network of EJ leaders have begun to demonstrate that the region is home to some of the most significant grassroots struggles for clean water and healthy communities. Mainly led by women of color, and many times performing labor that is unseen and unheralded, EJ leaders are building coalitions and networks, influencing policy, and working with young people to develop their leadership skills. Environmental justice organizations are partnering with universities to conduct community-based research, developing creative media to share their stories of resistance, and taking direct action when needed. They are also working for stronger alignment in the environmental movement and demanding that mainstream environmental organizations discard transactional attitudes.

But above all, frontline organizations are addressing state-sanctioned public health disparities and corporate practices that treat communities of color as expendable. They represent communities that are united by shared experiences of official negligence, and the knowledge that oppressed poeple must collectively steward a just transition towards economic and environmental vitality.

What urban leadership for clean water looks like

In Detroit, a city devastated by de-industrialization, local EJ organizations are at the forefront of fighting residential water shutoffs that are linked to patterns of urban displacement and exacerbated by emergency management practices. Building upon a strong Black radical tradition in Detroit, oganizations such as We the People of Detroit and East Michigan Environmental Action Council, among others, are working together to protect working-class Black and frontline communities from intensifying water, housing, and public health threats.

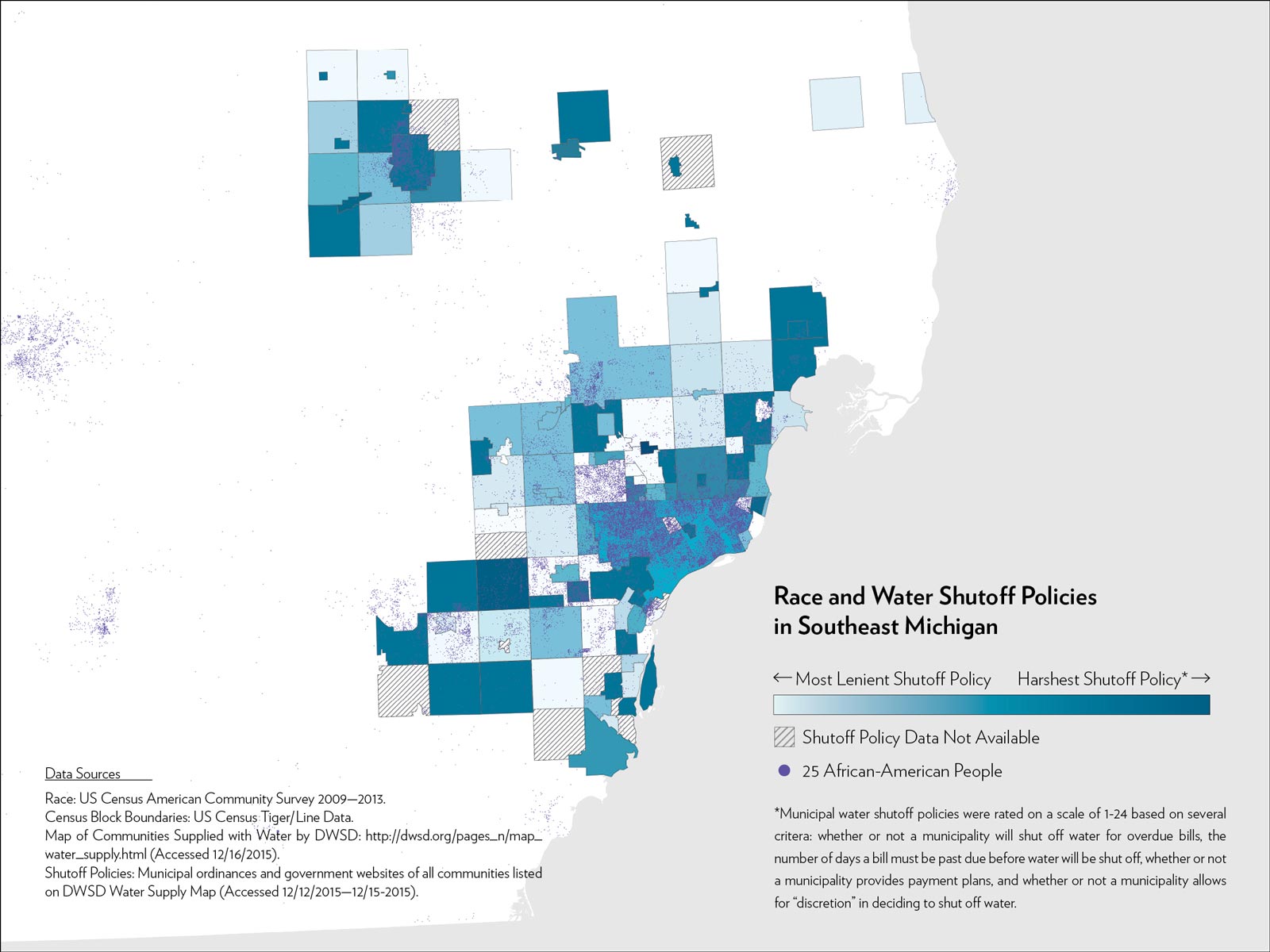

EJ activists in Detroit used maps to reveal a relationship between race and water shutoff policies. From Mapping the Water Crisis by We the People of Detroit

Grassroots activists have organized multiple forums and a People’s Water Board to “protect our water from pollution, high water rates, privatization; and the denial of water and sanitation services to people unable to afford it.” EJ leaders have also published Mapping the Water Crisis—the dismantling of African-American Neighborhoods in Detroit, and continue to support communities in Flint, Michigan who still endure lead contaminated water. Through community and youth organizing, cultural production, and community based research, Detroit based EJ organizations lead the country in re-envisioning the post-industrial metropolis.

• • •

EJ activists in Milwaukee are also forming new communities of resistance to fight lead contamination and ensure that the city government places equity at the center of municipal water policies. Aligning with The Campaign for Lead Free Water, grassroots leaders with the Fresh Water for Life Action Coalition are holding public officials accountable for comprehensively addressing lead contamination. In a July 19, 2017 open letter to the Milwaukee Health Department, EJ leaders wrote,

MHD (together with the Mayor and Milwaukee Water Works (MWW)) failed to put forth a comprehensive interim and long-term plan to mitigate and end the health harm from lead in the city’s tap water, it has also suggested actions that keep the people in the dark about the imminent risk of exposure and offer false assurances with nostrums about flushing and household testing.

In addition to struggling for clean drinking water, EJ leaders in Milwaukee are also at the forefront of equitable Great Lakes redevelopment and revitalization efforts.

Through community forums and townhall meetings, Milwaukee Water Commons has led the development of a Water City Agenda that aims to set priorities for a “community-defined vision for Milwaukee as a model water city.” According to the authors,

Although Milwaukee’s water is very much on the civic agenda, the vast majority of the city’s citizens are not included in the conversation and the health of the water is not always front and center. Milwaukee Water Commons believes that only by inviting leadership and innovation from throughout the community can we truly grasp what it means to become a model water city in all its dimensions and activate the level of community commitment necessary for achieving that vision.

Inviting young people and families to contribute to visioning and planning conversations, Milwaukee Water Commons exhibits an intergenerational approach to water activism and sustaining new and creative interactions with Lake Michigan.

• • •

And on the southside of Chicago, the home of Hazel Johnson, EJ leaders affiliated with the Chicago Environmental Justice Network are continuing the legacy of organizing for clean air, water and economic justice.

Working in Altgeld Gardens, People for Community Recovery teaches the community lead abatement techniques and advocates for the health of public housing residents who are often marginalized.

The Sacred Keepers Youth Council teaches gardening and urban ecology in Chicago.

Working with community members abandoned by the loss of manufacturing jobs, organizers with the Ban Petcoke Coalition and Southeast Environmental Task Force are waging an intense struggle to rid their community and local waterways of manganese and petcoke -- a toxic byproduct of tar sands oil refining.

And in the Bronzeville community, Sacred Keepers Sustainability Lab is leading innovative youth programming aimed at developing new generations of community leaders who are proud of their cultural traditions and deeply connected to the environment.

Finally, in Cicero the community organization Ixchel recently pushed the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District to mitigate hydrogen sulfide odors emanating from a nearby water and sewage treatment center.

• • •

It is important to note that the EJ organizations mentioned and the EJ-led struggles in Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee are only a few examples of inspiring EJ leadership taking place across the region. Indeed, throughout the Great Lakes Basin, grassroots EJ leaders and frontline communities are leading struggles against oil pipelines and fracking, and exposing the deadly links between extreme energy extraction and water contamination. It is also important to recognize that these struggles for clean water are often only one of the many environmental struggles that EJ leaders are leading in their communities.

What can we do?

How can environmental organizations, government agencies, and business groups better partner with frontline communities to address our nation's industrial legacy while building a resilient future?

→ Map the Hazards

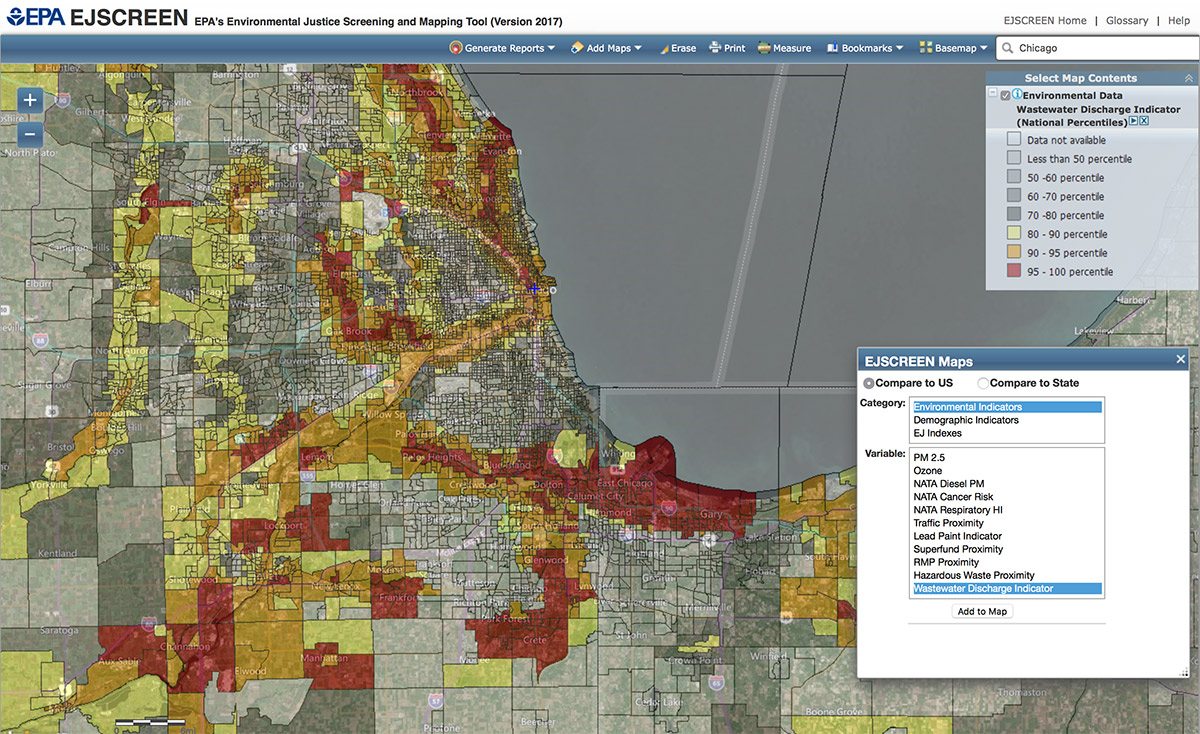

The maps available from EPA's EJ SCREEN system provide a way to view and search for pollution sources in your area.

Environmental inequality persists by hiding in plain sight. Creating a map of the environmental hazards in a region can reveal the not just the lines and systems perpetuating inequality, but also highlight the places that pose the greatest risks to people. Start by locating sources of industrial, municipal, or agricultural pollution, then follow these waste streams as they enter communities to map disproportionate burdens.

Our perception of risk is strongly influenced by personal experience and memory, more so than by statistics or data. Once you find the communities at greatest risk in your region, go visit them.

→ Support Local Leaders

If you’re worried about an environmental hazard, chances are there’s a group already organized around the issue in the community most acutely affected by it. Attend a meeting, and listen with an open mind. You might hear stories that change your perspective and spark creative thinking about ways to help.

Local EJ groups are often severely under-resourced compared to mainstream environmental organizations. One way to help is to hold a fundraiser or collect donations for community-based EJ groups.

→ Promote Equitable Solutions

Just as environmental hazards are rarely shared equally, the solutions offered by officials tend to perpetuate inequality. Programs that provide cleanup after disasters or infrastructure improvements are often designed to attract investment from real-estate developers and the business community. These programs should serve the people first, and be rooted in social responsibility to a community’s current residents. Learn more about the relationship between redevelopment and displacement so you can identify and resist false solutions.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories