Laws, Lies, and Lead in Water

Official stories about lead in our water often mislead us and place our families and communities at risk.

❖

By Yanna Lambrinidou, Jennifer Chavez, and Paul Schwartz

12 min read

LEAD

Act Now

↓When we turn on our taps to fill up a glass of water, a baby bottle, or a pot for cooking food, we don’t often think that this water may contain lead.

And although there is no safe level of lead in water, we rarely worry that our exposure to lead can be frequent enough or high enough to cause miscarriage, stillbirth, and irreversible brain and neurological damage, especially in fetuses, infants, and young children, who are the most vulnerable to harm.

The messages we receive from water utilities, government agencies, the medical, public health, and environmental health communities, and school officials – among others – tell us that lead in water is mainly a problem of “old” plumbing, that our water utilities address it through chemical treatments, and that in the rare cases when contamination does occur it is easy to identify and resolve.

However, communities across the US have discovered that the story of lead in drinking water is more complex and more concerning. In Great Lakes states such as Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, people are not only documenting problems themselves, but also organizing to demand short- and long-term solutions that protect their families and communities from harm.

A buried problem

The problem of lead in our drinking water is widespread for two main reasons. First, old plumbing with high concentrations of lead exists in the vast majority of US homes (urban, suburban, and rural). To this day most plumbing pipes and fixtures – even when they are new and labeled “lead free” – may contain some lead that can cause significant lead-in-water contamination. Second, the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), the federal regulation that was enacted in 1991 to protect us from lead at the tap, is inadequate, flawed, and outdated. On top of this, public and private water utilities across the US often fail to properly implement it, and it is rarely enforced by either state or federal regulators.

Melissa Mays of Water You Fighting For shares her personal experience of the ongoing water crisis in Flint.

Two historic crises illustrate the holes in the system meant to prevent health harm from lead in drinking water. Ten years after the LCR’s promulgation, Washington, DC – where the law was drafted – faced a two-and-a-half year cover up of unprecedented contamination from 2001-2004. And 23 years after the LCR went into effect, the 2014 crisis in Flint, Michigan revealed that the lessons from DC had not been learned.

More than 5000 US water systems are in violation of the law, but face little enforcement. Source: CNN Video

In both DC and Flint, affected residents first discovered the contamination and quickly took action to alert government agencies. The outcry of these residents was ignored and dismissed as the officials in charge claimed that all regulatory requirements were being met. Many of the same officials remained in power as the communities faced extensive harm. In Washington, DC hundreds (possibly up to 42,000) of children experienced lead poisoning, and the city’s fetal death rate increased by 37 percent. In Flint, incidence of elevated blood lead levels among children younger than five doubled.

Lead across the country

Official stories about lead in drinking water assert that Washington, DC and Flint, MI were exceptions. Evidence suggests that the problem is far more pervasive than the authorities admit.

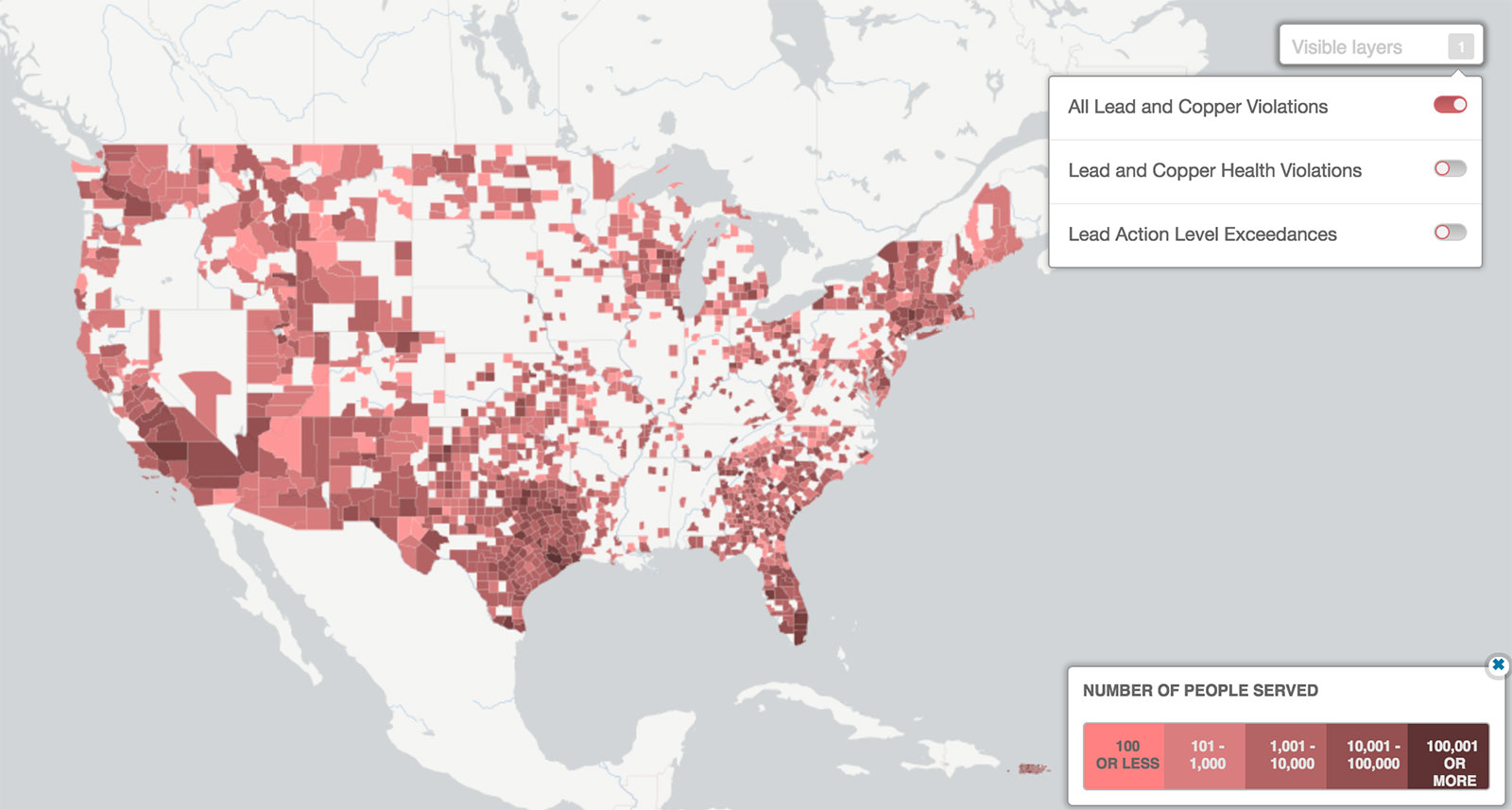

Millions of people across the country are affected by lead in water. Get information on Lead and Copper Rule violations in the US using this interactive map from NRDC

According to a recent study, if the LCR were to require water utilities to sample water in a way that catches worst-case lead levels at home taps, 54-70 percent of water utilities serving residences with “lead service lines” – these are pipes made of 100 percent pure lead that connect individual homes to water mains under the street – would discover widespread and severe contamination. Under this scenario, water utilities would be required to issue emergency public notification urging residents to take immediate precautions. Such a development could impact up to 96 million consumers who are currently told that their tap water meets all regulatory requirements and is safe for drinking and cooking.

Who is responsible?

The official line maintains that lead in drinking water is primarily the responsibility of homeowners because most lead-bearing plumbing runs through and serves private property . What these stories leave out is that this plumbing has been imposed on homeowners for over a century. In some cities lead service lines were mandated by law. For example, Milwaukee required their use until 1948 and Chicago until 1986, which is the year when these lines were nationally banned.

Lead-bearing plumbing is still imposed on homeowners, mostly without their knowledge, and can still leach significant levels of lead, even when it meets the federal requirement for “lead free” plumbing. Even today, it can be very hard to find and buy brand new metal plumbing fixtures that contain no lead or are guaranteed to leach no lead.

A corroded lead service line in Flint, MI. Photo: Caitlin Saks / WGBH

The environmental injustice of lead in our water is compounded by three disturbing realities:

The LCR places only partial responsibility on water utilities to control lead at our taps, making consumers partly responsible for protecting ourselves. At the same time, water utilities generally fail to inform us about this arrangement or ensure that we receive the necessary information to take effective precautions.

The very institutions with the responsibility, authority, and power to protect us from lead in water systematically disseminate inaccurate, incomplete, and misleading information about the relevant science, health risks, and public policy. This phenomenon manufactures a collective ignorance, which diminishes our power to protect our health, to participate meaningfully when decisions are made, and to hold our public officials accountable.

Rising water bills in communities across the country squeeze many low-income residents into decreasing their water use, or leave them unable to pay and vulnerable to water shut offs. Detroit, for example, a city with more than 125,000 lead service lines, has experienced one of the nation’s most severe drinking water shut-off programs. But low water use and prolonged water stagnation can cause lead to disintegrate, detach from pipes, and fall into the water we use for drinking and cooking. Especially in homes with lead service lines, this can pose an immediate and acute health risk to us, similar to the risk of ingesting chips of lead paint.

What stands in the way of just solutions?

Current laws governing lead in water are centered on the wrong priorities, elevating private property rights while de-prioritizing public health. Regulatory agencies, water utilities, and even public interest non-profit organizations have assigned an inflated significance to the division between public space and private property, artificially separating responsibility for maintaining a safe drinking water system between governments and utilities on the one hand, and private residents on the other.

People walk along Saginaw Street on Flint's north side past a sign for water being given away at Mt. Calvary Missionary Baptist Church in Flint. The church started handing out water donated from throughout the United States and Canada twice-a-week to people in need and small churches. Photo: Ryan Garza / Detroit Free Press

This sets up a stark imbalance of power whereby public entities have broad authority to regulate and control lead service lines running through private property (by requiring homeowners to implement specific upgrades to existing service lines), while private residents have very little independent control over these lines, imposed on them decades ago.

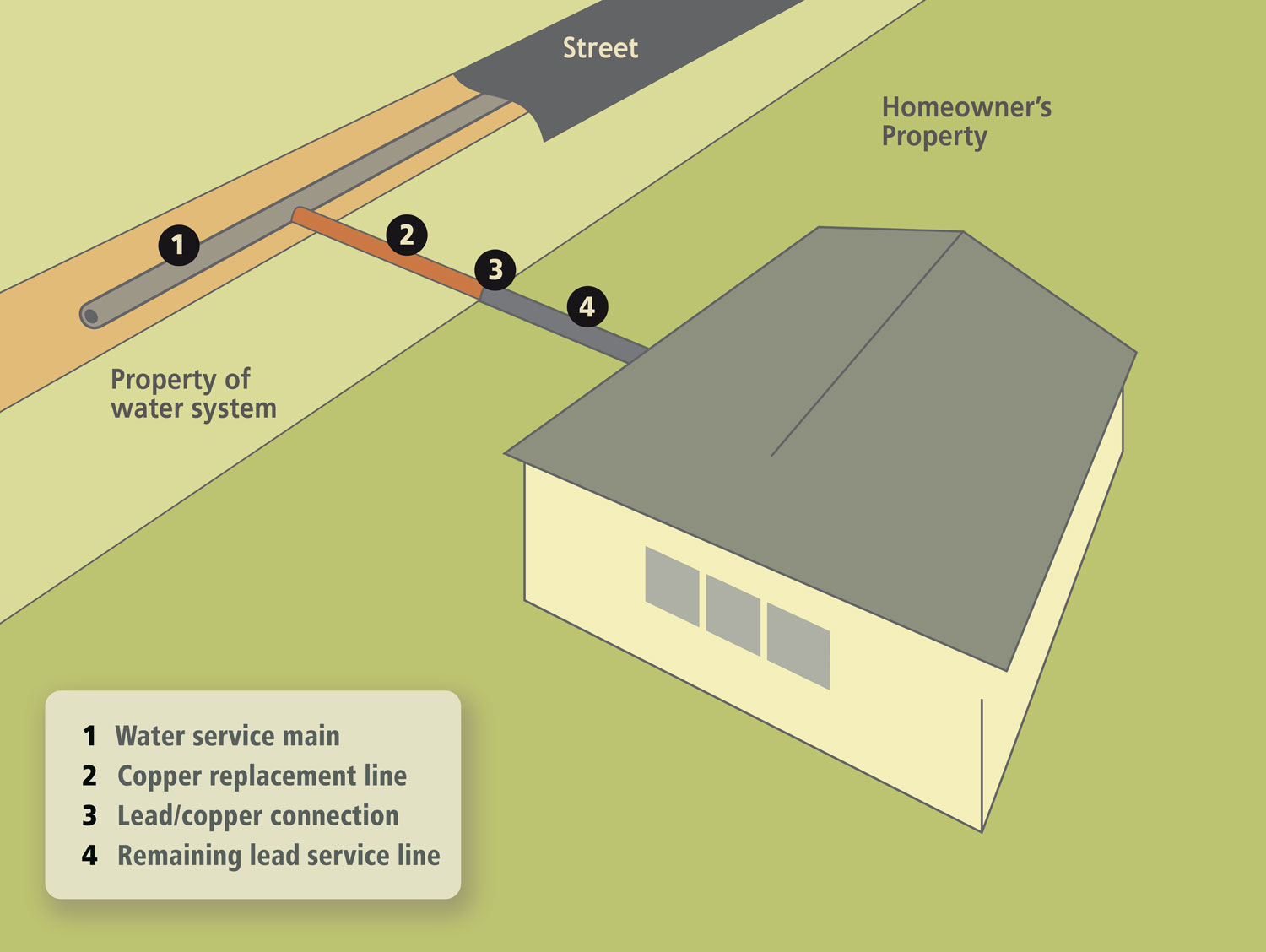

On this basis , when water utilities dig up streets to replace or repair water mains and encounter a lead service line, they usually replace only the portion of the line between the water main and the property line. These partial lead service line replacements take place across the US on a daily basis – often with no notice to residents – despite the fact that they have been found in certain circumstances to increase residents’ risk of exposure for days, weeks, months, or even years.

Milwaukee Public Works Department crews repair a break in the city-owned section of a lead service lateral between the water main and a private property boundary. Photo: Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), children in homes with a partial lead service line were twice as likely as children in homes with an intact lead service line to have elevated blood lead levels, and four times as likely to have elevated blood lead levels as children in homes with no lead service line.

Currently, most water utilities conduct full replacements only when homeowners agree to pay between several hundred and several thousand dollars to cover the remaining cost of the replacement. This scheme places a great burden on residents who had no role in or responsibility for the installation of lead service lines in the first place. Worse, it turns a blind eye to the many low- and moderate-income homeowners who cannot afford such a large unplanned expense. This patchwork approach is costly, inefficient and leaves many at risk.

Initially the Lead and Copper Rule required water utilities to replace entire lead service lines if they had "control" over the lines, as most utilities do. In response to a lawsuit and pressure from the American Water Works Association (AWWA) challenging that requirement, in 2000 the rule was revised to allow for partial replacements. As a result of AWWA’s pressure, for the past 17 years the vast majority of lead service line replacements under the LCR have been partial replacements. Image: Matthew Ray/EHP

The good news is that the popular preoccupation with private property rights is neither justified nor compelled by the prevailing legal principles. The claim that homeowners own lead service lines is highly questionable. Because those lines are integral to the water distribution system and serve no other purpose than the delivery of drinking water, service lines are legally defined as part of the public water system regulated under the LCR.

Even assuming that lead service lines are privately owned, the hyper-focus on property lines is unjustified. It appears to grow out of a mistaken belief that the overriding purpose of private property is to enforce the owner’s right to exclude non-owners from the property. To be sure, many elected officials and a few legal scholars embrace this belief. But even the most conservative scholars acknowledge – and courts agree – that government entities, and the public water utilities they own or regulate, enjoy broad authority to enter onto private property in order to protect public health.

What can we do?

In the dominant stories about drinking water systems, property owners’ right to exclude non-owners is weaponized against them and, critically, against all of us, especially minors and other non-owners living on the property. Dividing responsibility at the property line diminishes the water utilities’ duty to undertake full lead service line replacement, and promotes the false idea that private residents have caused, and are responsible for, their own health harm. This ideological viewpoint has very likely resulted in millions of dangerous partial lead service line replacements, absent homeowner knowledge or true informed consent. It has also allowed the still-ongoing installation of lead-bearing plumbing in our homes. If we want to build a future where all our plumbing is truly lead-free, we must move beyond this morally bankrupt framework.

→ Take Immediate Steps to Prevent Exposure

Given that lead-bearing plumbing is prevalent, it's safe to assume that any tap you use for drinking, cooking, or making infant formula may dispense lead at any time and of any level, no matter how it tested during any one-time sampling. Because lead from plumbing tends to release erratically and in dramatically fluctuating concentrations, one-time tests should not be used to determine if a tap is “safe” at all times.

Look for this symbol when shopping for a lead-certified filter.

To prevent exposures, use a lead-certified pitcher-style filter or install a lead-certified filter at your faucet. For maximal protection, your filter should meet the NSF/ANSI 42 standard for particulate Class I reduction and the NSF/ANSI 53 standard for lead reduction, and should be maintained and replaced according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

→ Speak Out Against Misinformation

When you hear officials – face-to-face or through the media – speak about lead, make sure they're providing accurate information. When they don't, speak out by reaching out to them, writing a letter to the editor, posting a comment on social media, or taking another action requesting a correction. A resource that might help in this effort is The Top Ten Myths About Lead in Drinking Water.

You can also get detailed, accurate information on Lead and Copper Rule violations in the US by water district using this interactive map from NRDC.

→ Demand an End to Lead in Plumbing

Say “No” to new fixtures containing lead. Unfortunately, while lead content has been greatly reduced in our nation’s plumbing, it is still allowed in the products sold by hardware stores today. The persistence of lead in plumbing fixtures stands in contrast to gasoline and paint, which are available lead free. This perpetuates the substantial risk that the water we use for cooking and drinking contains lead.

It's time to get the lead out of plumbing once and for all. When you're in the market for new plumbing, contact manufacturers and sellers and request plumbing materials with zero lead. In the meantime, consider advocating for the adoption of disclosure laws in your state that would require the delivery of complete and accurate information about lead in old and new plumbing to new tenants and buyers.

Press your water utility to stop partial lead service line replacements permanently and to pursue a proactive full lead service line replacement program. Cities like Lansing, MI; Madison, WI; and Philadelphia, PA have found ways to perform and fund full lead service line replacements, and Michigan has just proposed a regulatory requirement for a statewide proactive full lead service line replacement program. The lessons learned from these initiatives can help create even stronger replacement programs in other communities.

Consider launching a campaign to remove regulatory barriers to full and just lead service line replacement at the local and state level. At the same time, remain vigilant against pushes by the government, private industry, or academia of alternatives to full lead service line replacement that are presented as quick, practical, or more affordable “solutions” but that, in reality, are unproven band-aids. Epoxy lining of lead service lines is one such example.

Remember that the LCR is a “shared responsibility” regulation, and yet the people who make decisions about how it is written and how it is implemented on the ground rarely, if ever, hear the views of residents with small children, individuals who have been harmed from lead in drinking water, or members of communities with inadequate resources to protect themselves from exposures. These voices – our voices – contain knowledge that experts often lack. For this reason, they belong at the center of decisions about short- and long-term solutions, and are essential for ensuring that such solutions are health protective, locally appropriate, and environmentally just.

Freshwater Stories

Freshwater Stories